Copula Hall

GSAPP Adv. VI Studio - Government - The City & The City, by China Meiville

visualizing redundancy in fictional sovereignties

2020

in collaboration with…. Morgan Parrish

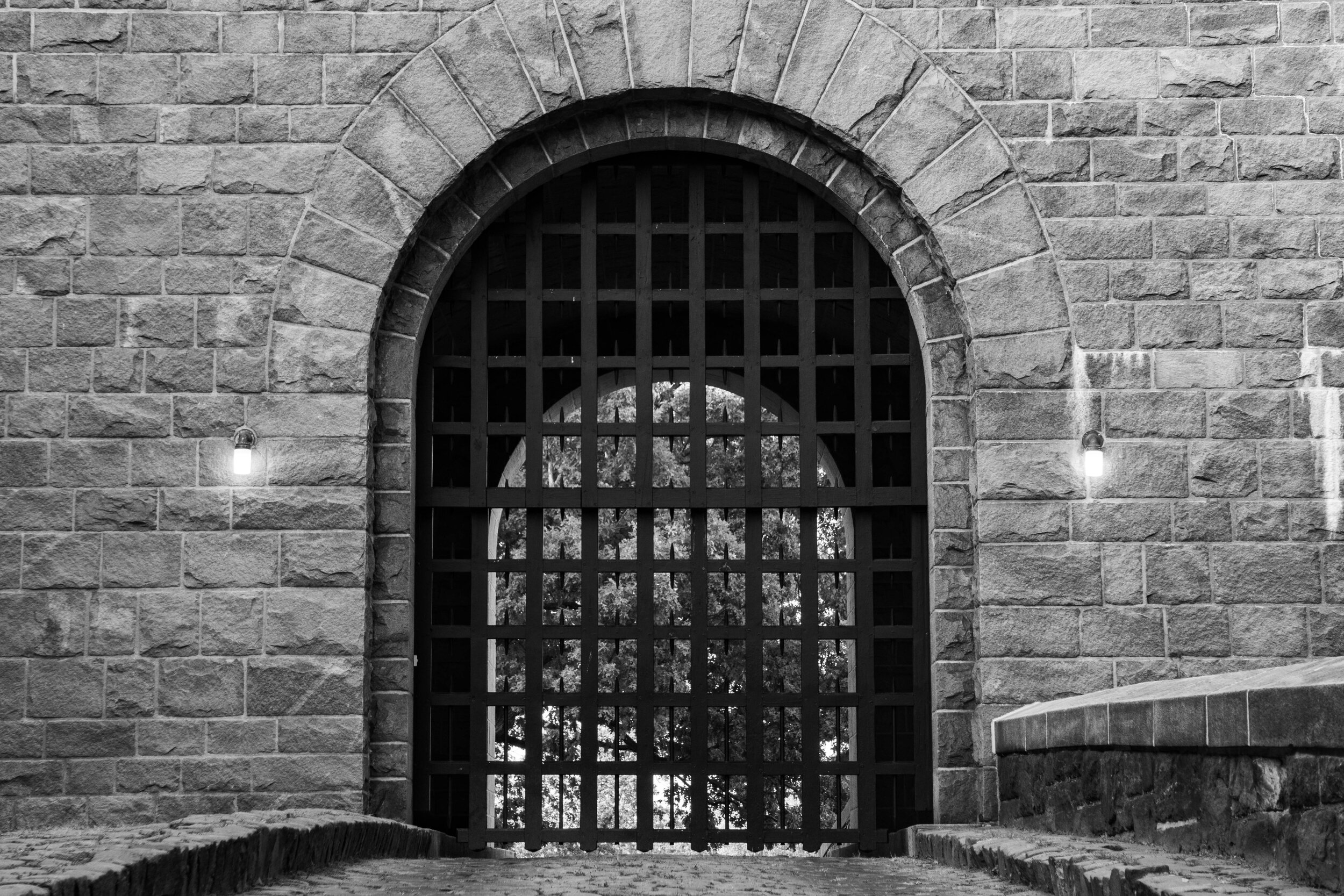

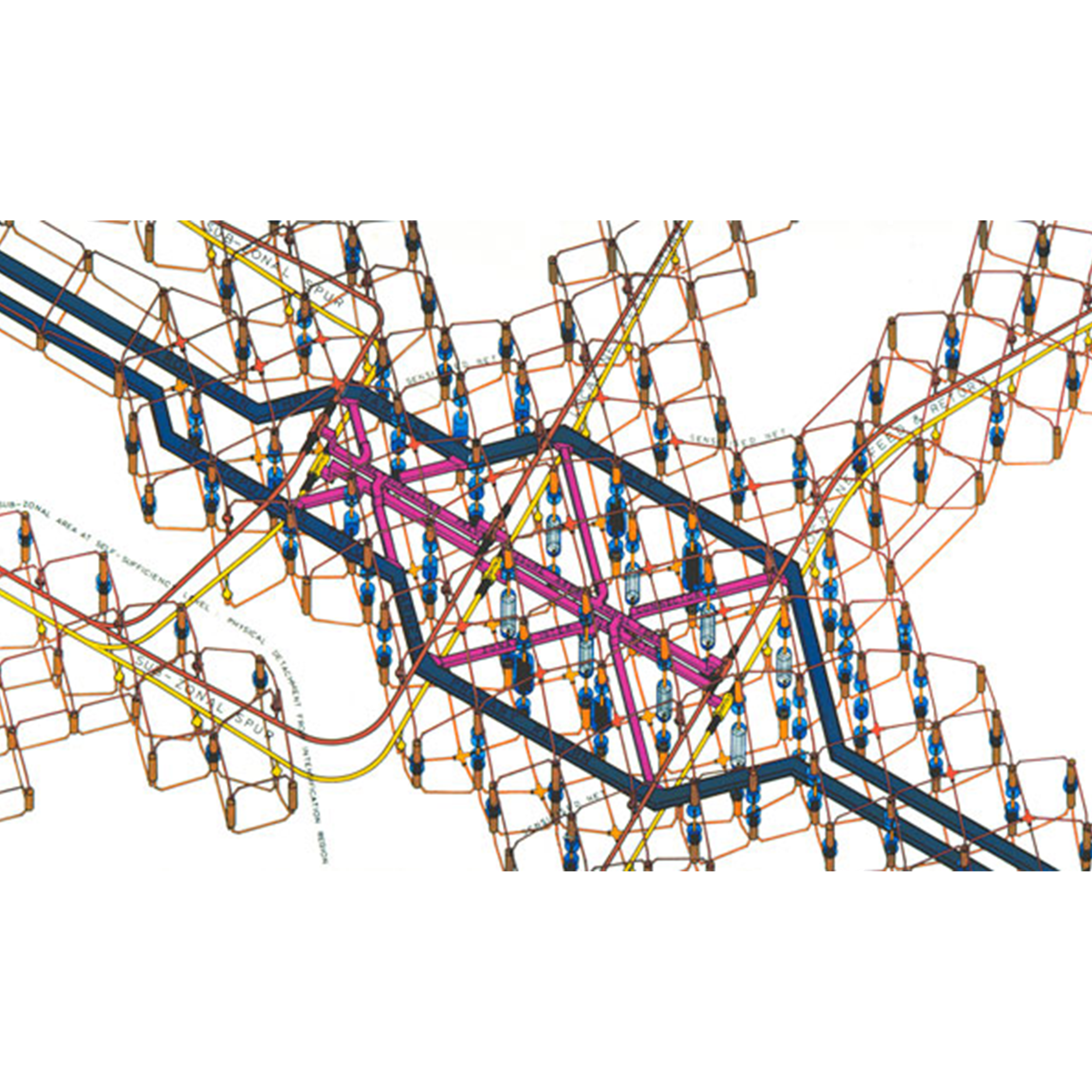

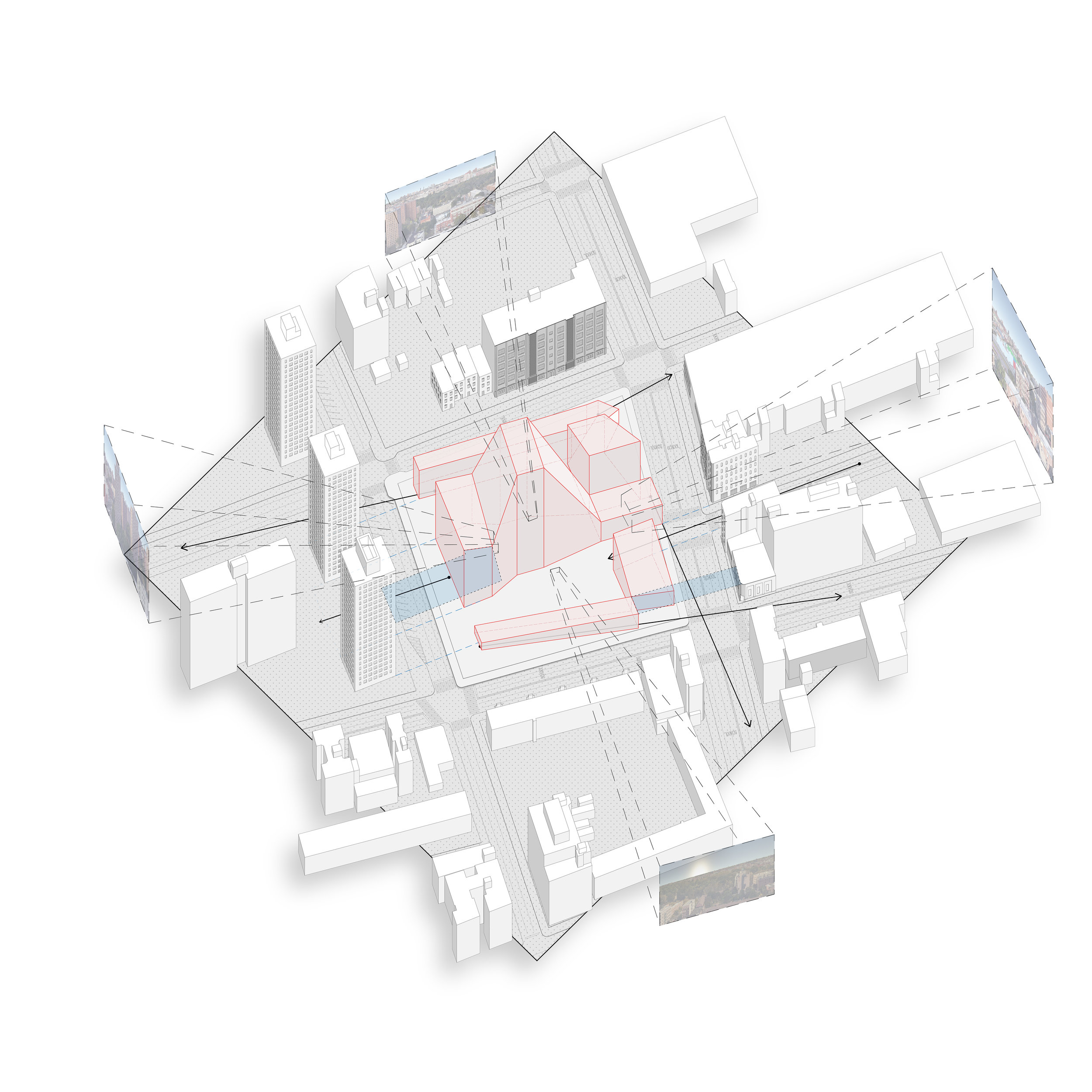

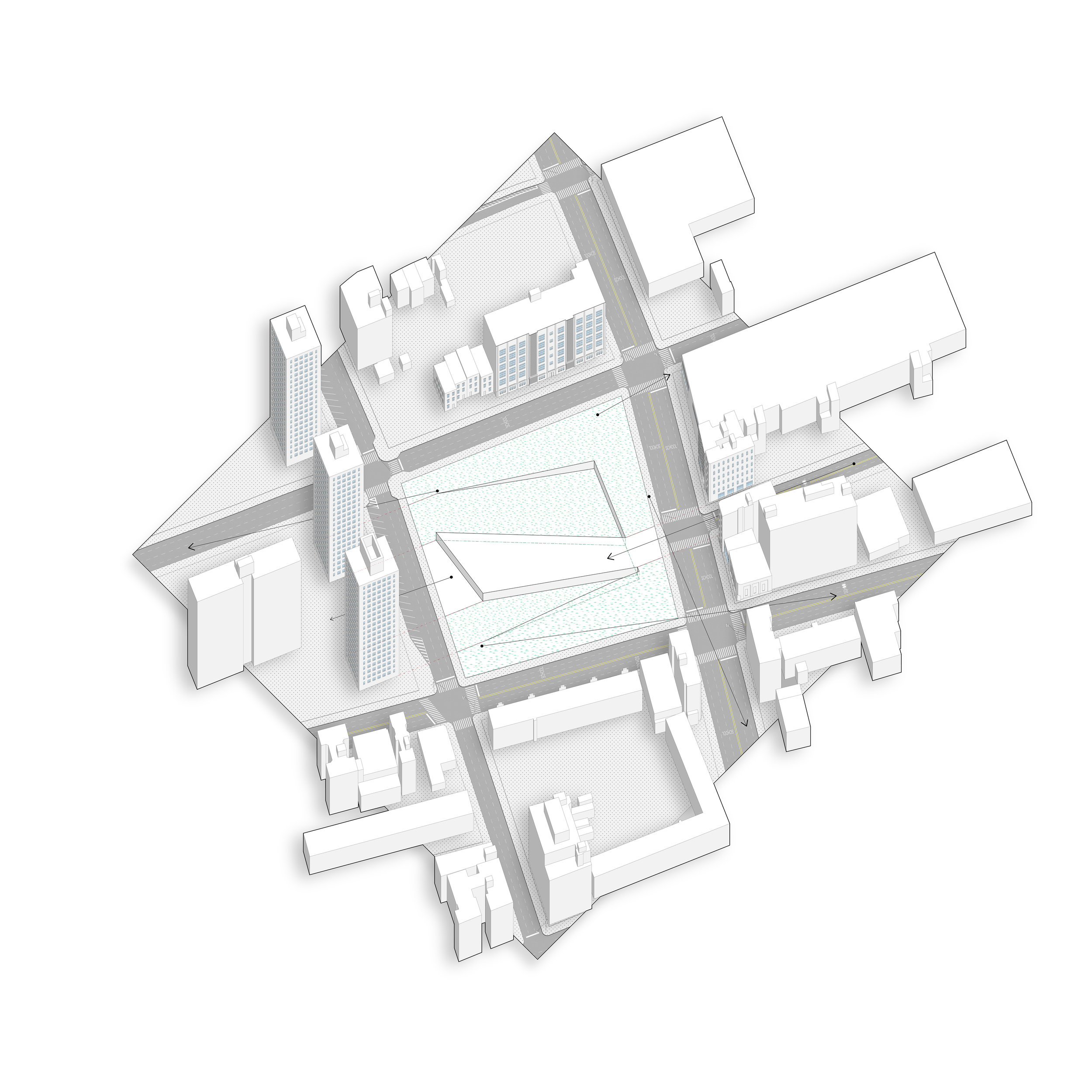

China Mieville’s novel The City and The City echoes a thematic redundancy in names, actions, and spaces. The literature subvertly highlights a woven inefficiency of movement as it follows characters and events forced to navigate two cities at once. Though they reside in the same geographical location, Beszel and Ul Qoma exist as separate entities that require an overlapping array of multiplicity - there exist two cafes, two transit systems, two economies, two governments. This repetitive duality plays out on a complex and intricate scale in Copula Hall, the single building that houses the collective and individual government and border checkpoints for both cities.

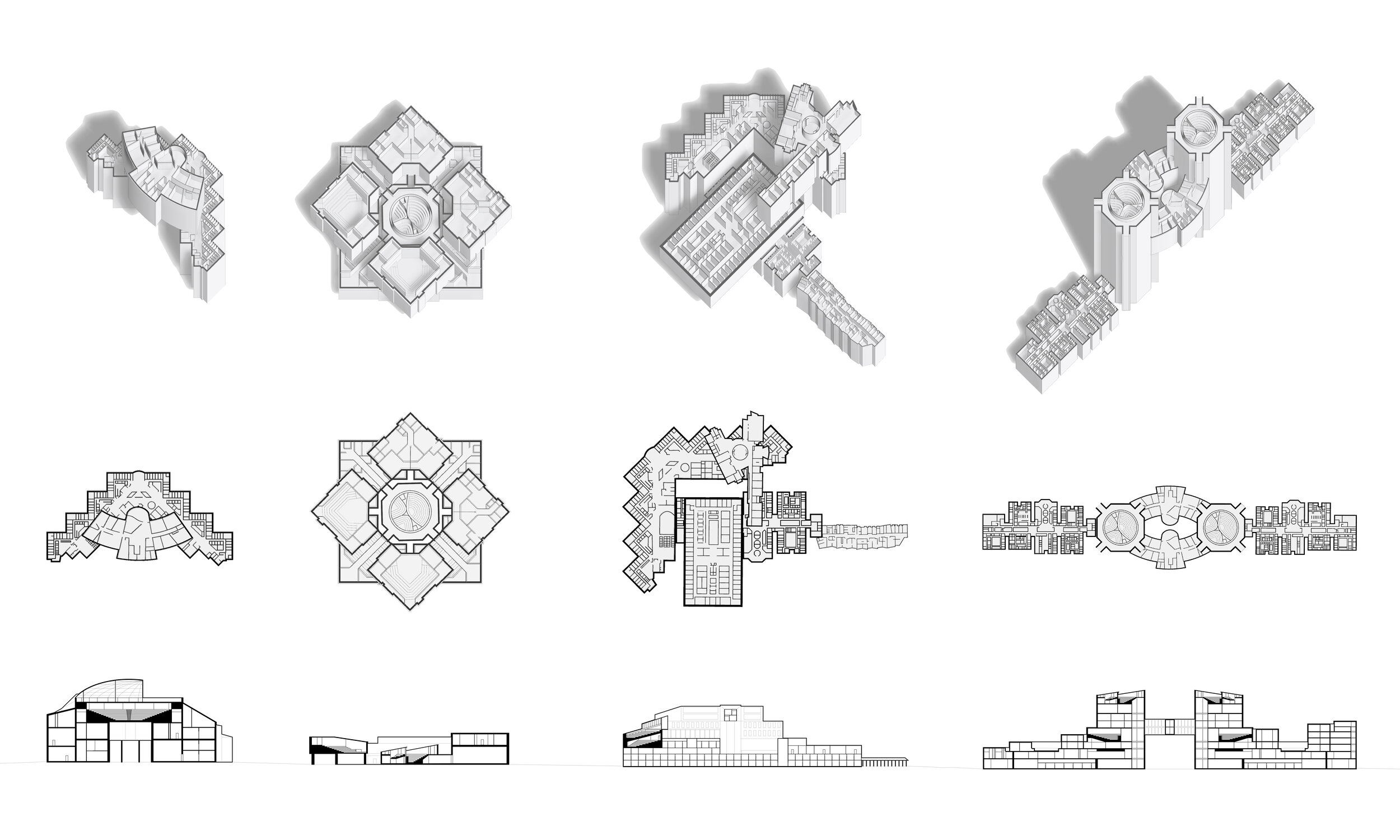

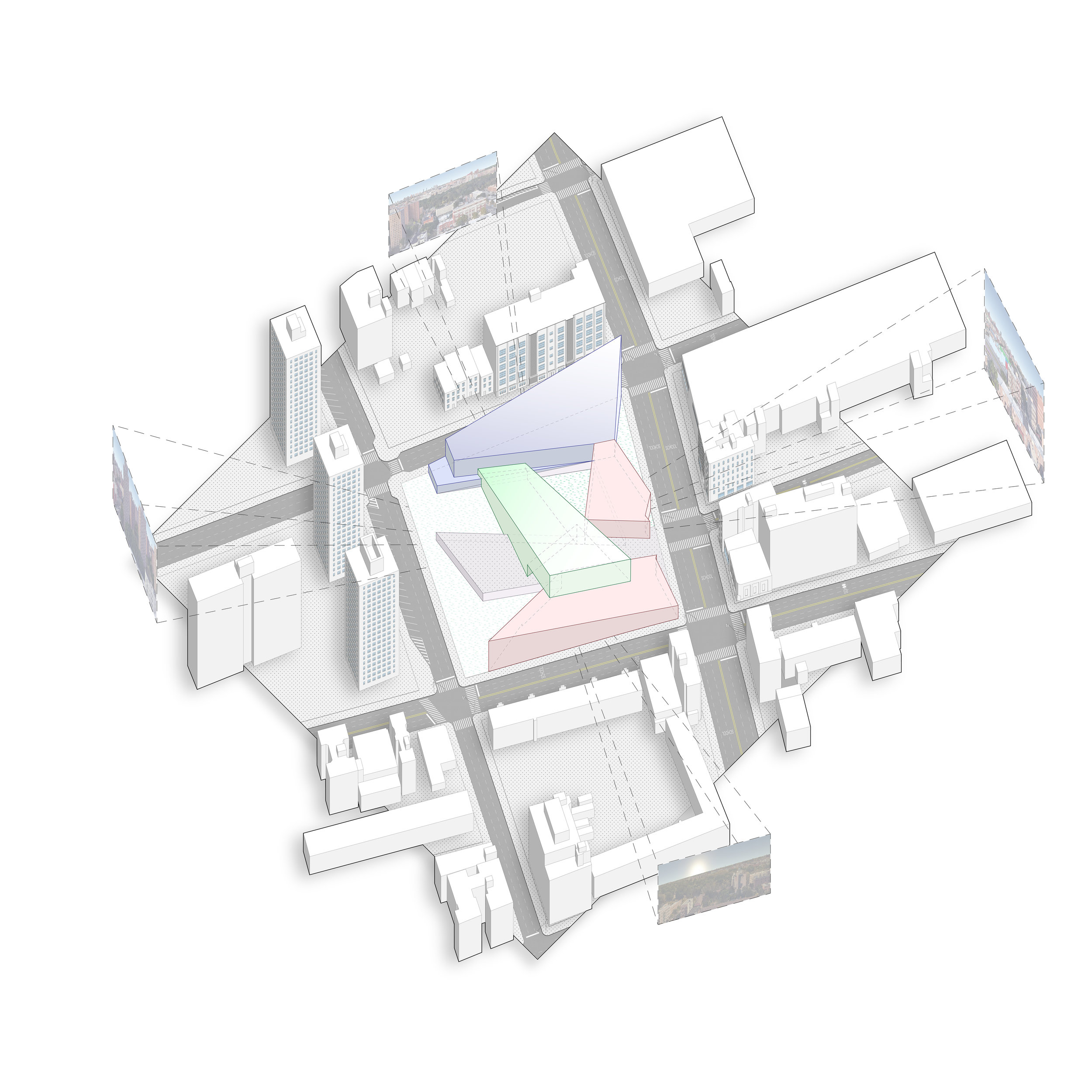

The design for Copula Hall seeks to formally and spatially play up this duality and highlight both the inefficiency that it might cause, especially in crosshatched interior spaces, and the experience of “seeing double” that one might feel within the city. Two large volumes are mirrored around a central point along the East-West axis - the gateway’s main thoroughfare - to create the focal points of each city’s domestic governments; with one volume for Ul Qoma and housing its Parliament and the other for Beszel and housing its City Council, each volume faces its own city’s entry point and acts as a welcoming facade for its denizens.

Viewed from the side, the two mirrored volumes are joined by crosshatched forms containing office spaces and international government chambers. Belonging to neither city, these volumes instead address the sameness of the cities - their equality in their duality - and create an intensely and chaotically bureaucratic environment totally shared by both cities. Ultimately Copula Hall exists not just as a government building, but as a symbol throughout both cities of their separation.

Mieville’s novel is set in the two fictional cities BESZEL & UL QOMA. The two independently sovereign city-states operate in dissent & unison with one another atop a densely packed urban infrastructure. Both cities occupy the same geographic area, laying claim to various sections of city to create a politically fragile ecosystem of interwoven borders – more often than not, quite literally crosshatching across one another spatially. Beszel & Ul Qoma are neither shared cities, nor split cities, yet something altogether unique and unprecedented.

The Edifice,

a companion narrative, by Jack Lynch

The coolness of the masonry edifice welcomed Safiye in the Grand Entrance of Copula Hall’s Ul Qoman wing. Had the university let her, she would have avoided the Hall altogether; but business was business, and the Ul Qoman archaeology archives - limited as they may be - happened to have that one unique artefact vital to her research.

The tapping of her stilettos reverberated along the narrowing hallway of stone as Safiye ascended the Grand Stair. She took her time, pausing for moments to study the line of various Pre-Cursor artefacts along banisters. One display, an outdated building apparatus, consisted of four various pieces that somehow connected together by means of a field of various finger-like appendages. Utterly bizarre.

Safiye pulled her eyes back from the display to check her watch. Shit. She was late for her appointment with the head archivist. With haste, Safiye pranced up the stairs.

Business as Usual,

a companion narrative, by Morgan Parrish

He cleared his throat from his seat at the end of the Council table, hoping it would quiet the bickering of his fellow Council members.

The topic for discussion today and the presentation provided by the citizens had been controversial and impassioned, and while the citizens, journalists, and reporters eagerly awaited the ruling of the City Council, the Council members sat around their long table and debated. It was not unusual - often the Council had difficulty reaching a consensus, and votes were usually rather split. The spectators and reporters had grown accustomed to sitting in the upstairs viewing galleries for long periods of time awaiting results.

He could hear the sound of rain beginning to patter against the skylights and the slim window behind him. Peering out through the slit and into the city, he saw people begin to open umbrellas. He hoped this matter would be resolved soon, as the grand staircase he walked to enter the Council Chamber tended to become precariously slippery when wet.

Office Life, a companion narrative, by Morgan Parrish

It was my first day working for Beszel’s Department of Transportation, and I was nervous. I had seen Copula Hall often, but I had never entered its doors. I exited the tram stop, crossed the plaza, and entered the glass doors into the crosshatched floor of open offices. To my untrained eyes, it was quiet, oddly ordered chaos.

A woman directed me to my desk, which shared a column with two Ul Qoman workers. I couldn’t help but feel that they, and by extension, that ‘other’ city, held total control over my future space. My fellow transportation department employees sat a few columns away - the director told me that, due to an overlap with an employee who would be leaving soon, I had to take the closest open desk, but that I would be able to sit with them in a more Besz section soon.

There seemed to be a subtle grouping of departments. Three Besz desks around a column, or a cluster of Besz desks all back to back - amongst the otherwise scattered employees of both cities. A natural order established by our rhythmic, patriotic sensibilities. I could tell that it would take a few months of working here to fully understand the radical nuances of this life.

Process Work….

Play House

GSAPP Adv. V Studio - Childcare - Jackson Heights, Queens, NY

an ethical childcare facility

2019

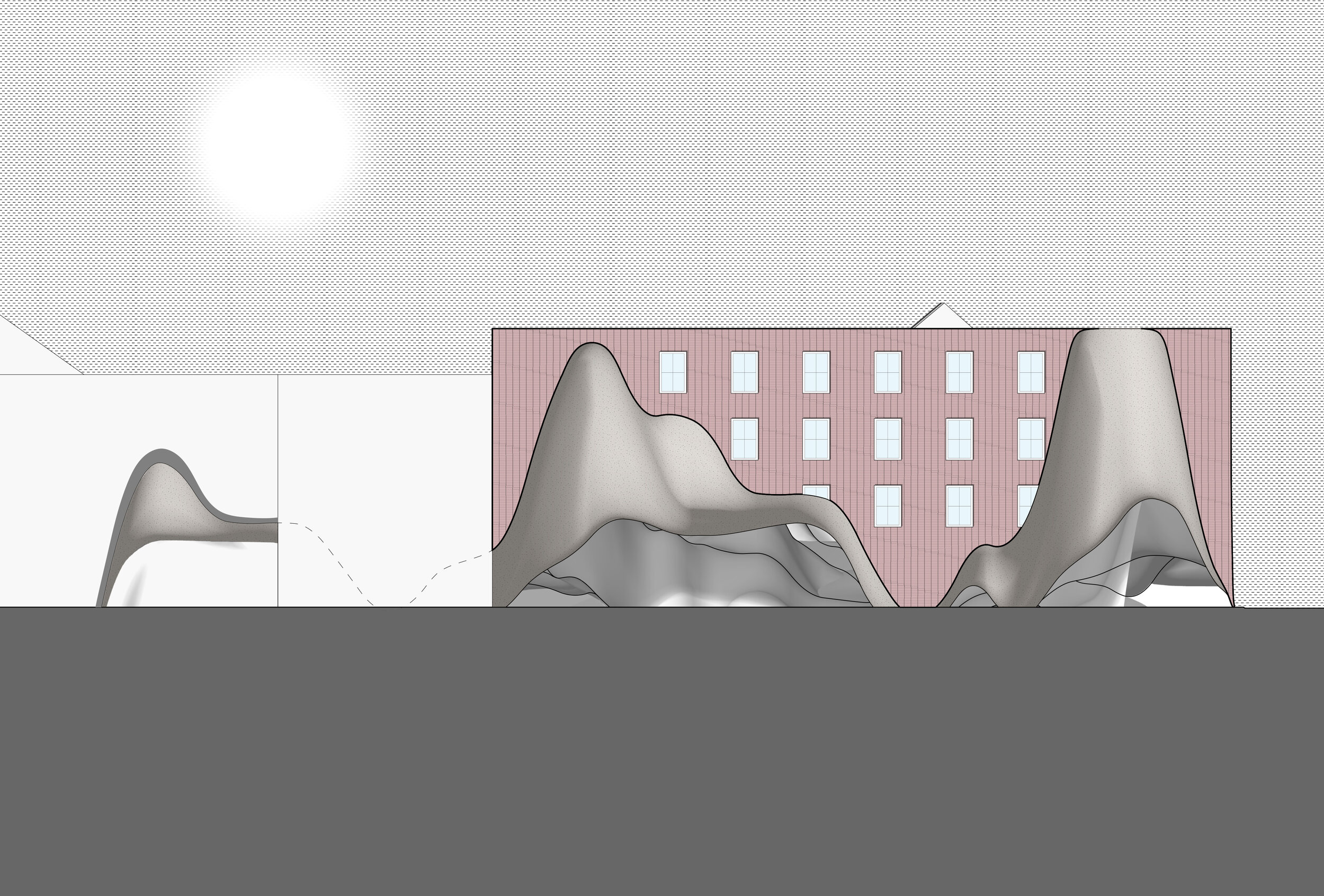

This new childcare facility manifested itself with a design focus on materiality as the backbone of the project, underscored by the foundational question: “how can the ethics of care be achieved holistically in design?” The facility is comprised almost entirely of cork, a miracle construction material with acoustic properties to shield children from the noises of passing overhead subway trains and vibrant Jackson Heights, Queens street life.

The compression qualities of this playful, non-toxic, water-resistant medium greatly influenced a building typology entirely funicular in its structural form. The result is a series of self-sustained compression vaults and undulating cork-paneled surfaces that weave together classrooms and additional childcare programs across interior and exterior spaces to establish areas of both play and protection.

Play house is rooted in an ethical framework internally and externally, with a community engagement for the Jackson Heights neighborhood by becoming a Community Land Trust (CLT) model for a neighborhood actively fighting gentrification and dwindling support.

Wellness House

GSAPP Adv. IV Studio - Healthcare - Newburgh, NY

an urban gesture towards nature & wellness

2019

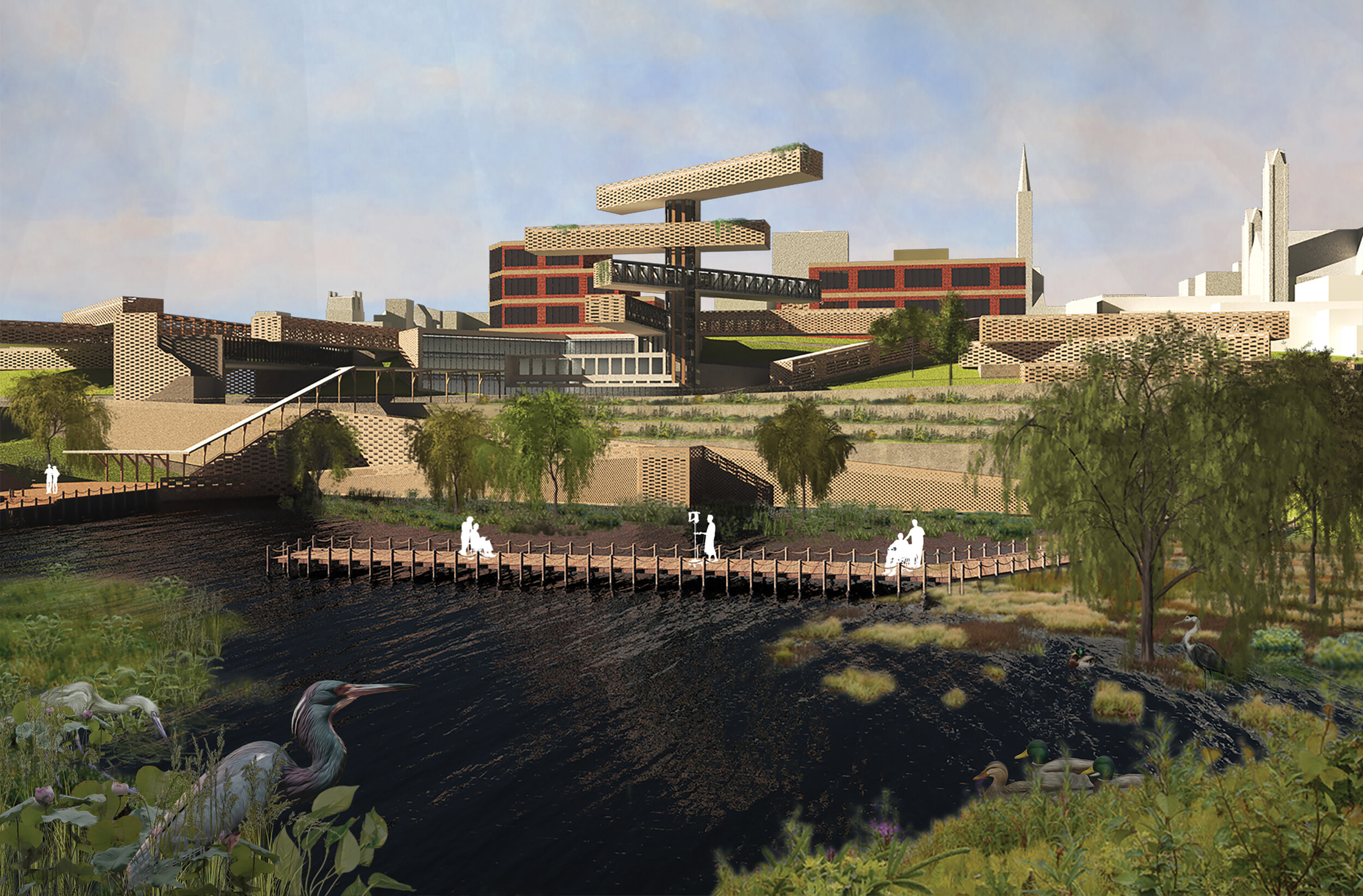

This urban development masterplan project sees a potential future for Newburgh, NY to become a thriving medical center in the Hudson Valley area.

Taking inspiration from Alvar Aalto’s Sanitorium and exploding it into an array of formal gestures that activate a difficult riverfront site, this future Newburgh Medical Campus aims to bring together urban and ecological systems in a healthy way. The hospital functions primarily as an inpatient oncology center and maternity ward, serving neighborhoods along the Hudson River with higher-than-normal testing rates for the respective healthcare specialties.

In-stay patients located in wards that weightlessly hover over the riverfront wetland landscape and surrounding tree-tops are invited to embrace the scenic beauty of the Hudson River and its natural awe. Here, the hospital, wellness house, is re-imagined as a tree, with branch-like wards being pre-fabricated modules that may be built upward and attached to a single trunk of vertical circulation. Alternatively, the same modules may be dispersed along the riverfront for extended medical infrastructure.

This new hospital typology pushes the limits of our understanding of how architecture can subvert existing medical connotations to establish healing spaces of human wellness.

Process Work….

Projected Living

GSAPP Core III Studio - Housing - Bronx, NY

curating visual queues in urban housing forms

2018

in collaboration with…. Jake Gulinson

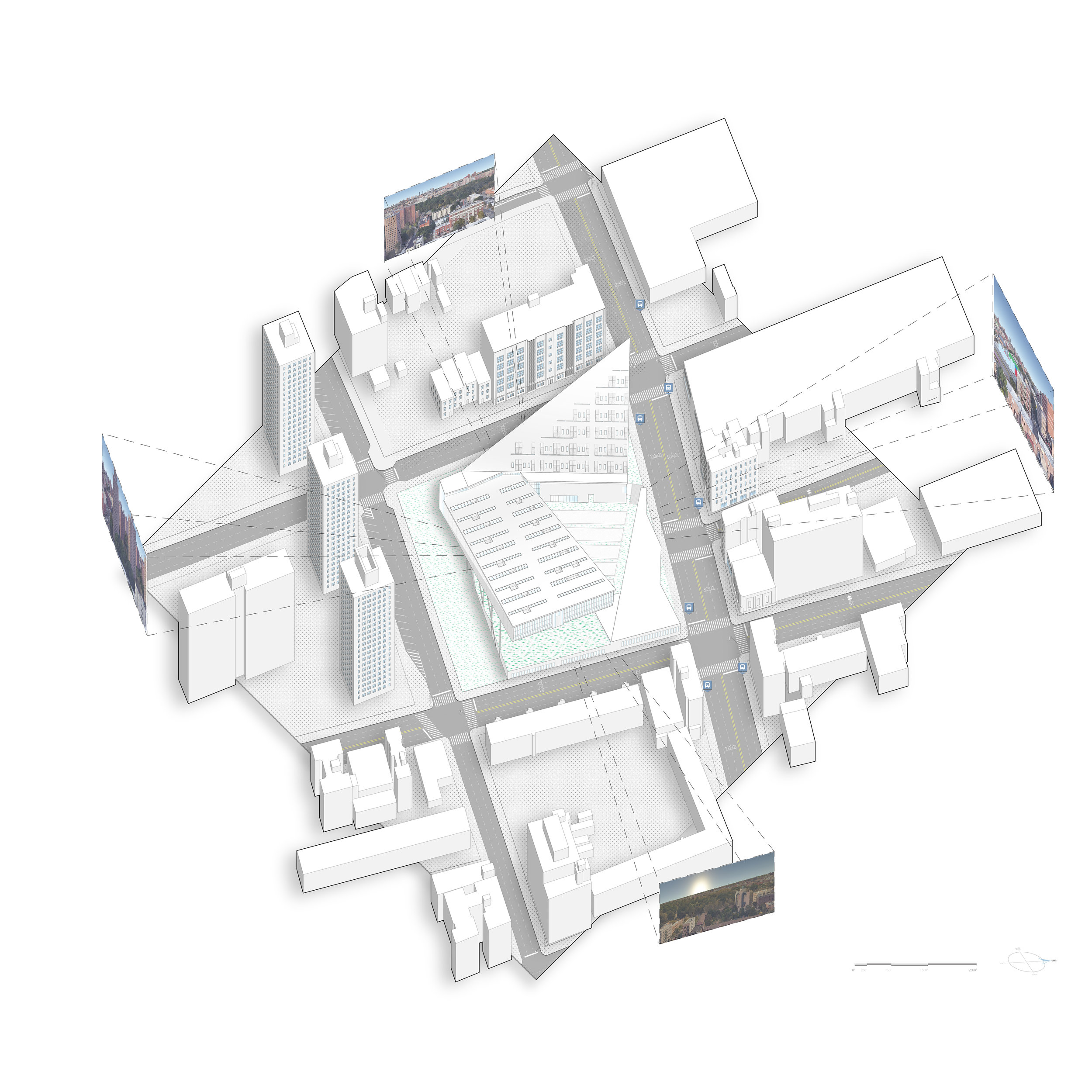

A complex housing project located in the Bronx, projected living began in an exploration of housing forms centered around the perspective viewpoints of occupants located both inside and outside the potential dwellings. The pivotal relationship between interior and exterior led to the driving question of what it means to see and be seen in an urban setting, and - more importantly - how does one live in such unique situations.

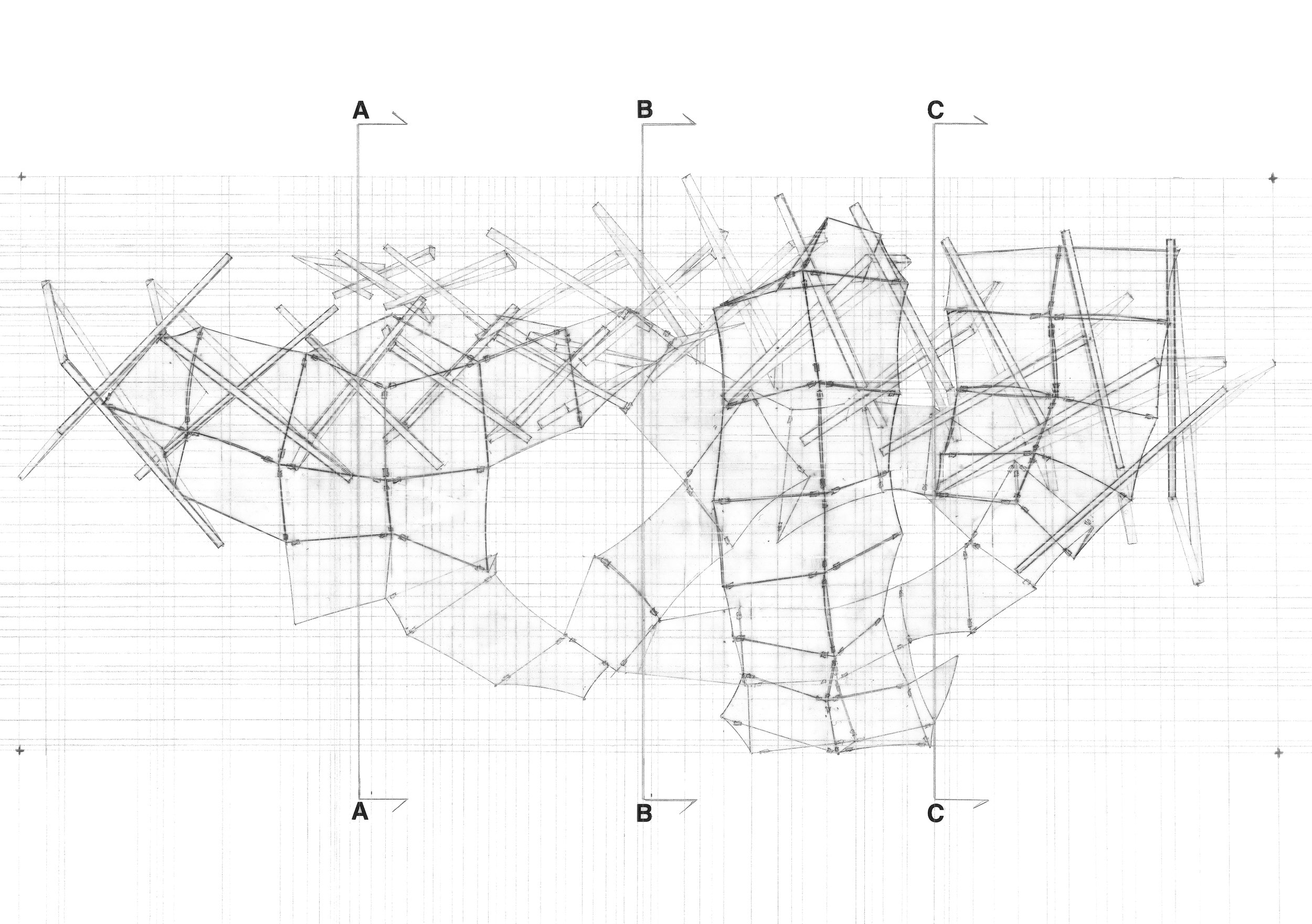

To further advance the larger mass of the multi-use development, forms were established first by means of designing in perspective. In this approach, formal architectural moves in plan and section were subjugated to the perception of space in real-time instances, from both inside the unit to the views of passersby along adjacent streets. Large scale moves were further influenced by vistas and viewpoints of direct relationship with urban site.

The project plays host to approximately 225 units following a modular taxonomy of 8 unit modules interspersed between the two largest vista masses, the north and south towers. Both towers rely on an intricate interplay between units and their larger truss structures, seamlessly creating impressive architectural moves that canopy the flatter portions of the site. Community programs such as a neighborhood YMCA, a fresh-foods grocers market, and day-care centers occupy these undulating sidewalk facades, ultimately pushing and pulling the perspectives of the streetscape.

Process Work….

Memory House

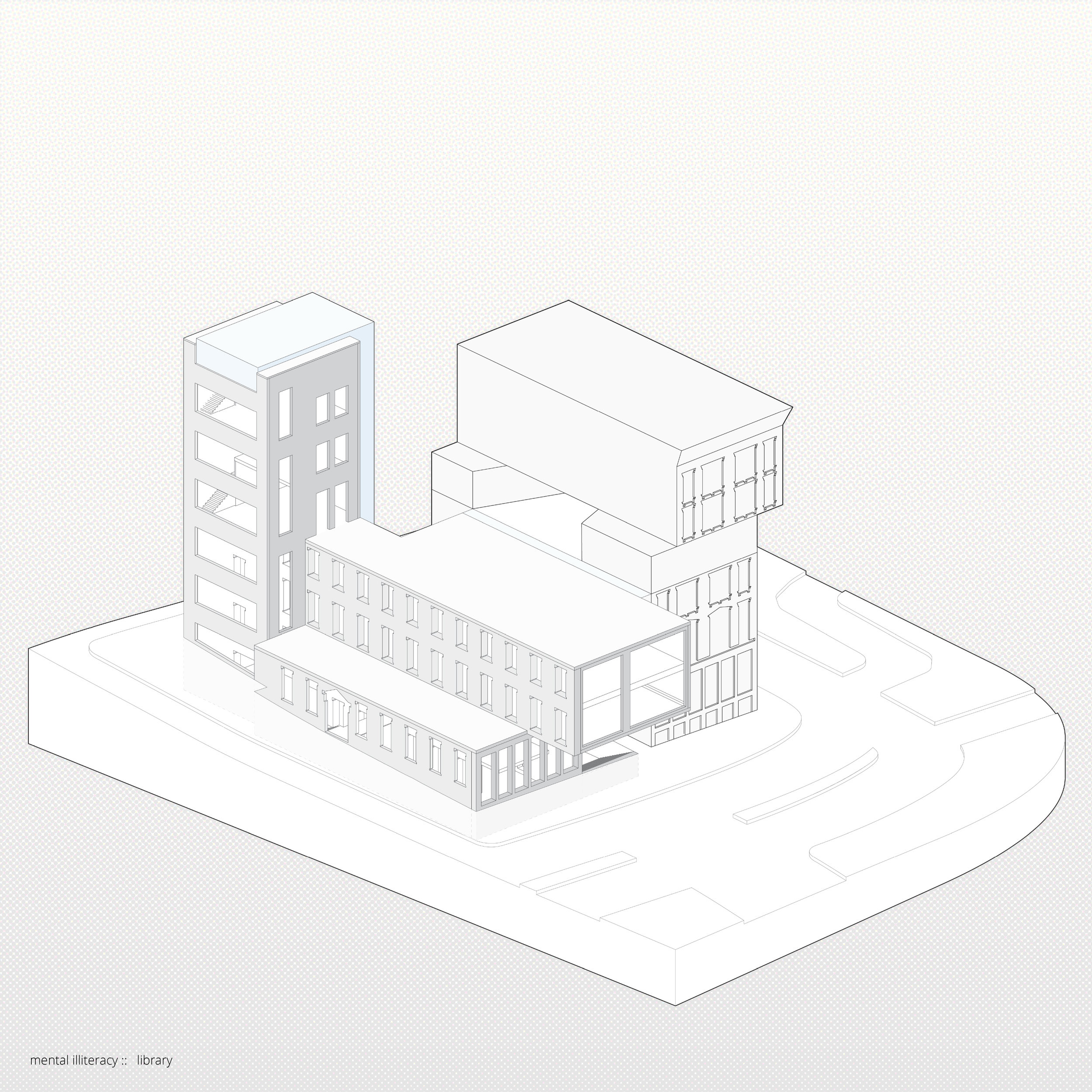

GSAPP Core II Studio - Library - Brooklyn, NY

library for mental illiteracy

2018

An illiteracy of the mind – of knowledge, memory, emotion, and life; of all these things and more that meet at the crossroads of what it means to live – is an unavoidable truth. We are all illiterate in this regard.

In order to establish a library devoted to the collection and representation of the intricacies of mental passageways and the human condition to remember, the proposed site, just off of the East River in DUMBO, Brooklyn, was continuously toyed with in a playful manner. Stepping back as a designer and recognizing the existence of a local memory via the contexts of the site allowed for a flexible amalgamation of nearby facade, window, ornamental, and structural systems that could be reinterpreted into a block-mass building capable of skewing the perceptions of visitors who may or may not have memories associated with the site.

Formally, the interconnecting block system allows for spaces to coexist in multiplicity. Exterior walls break up interior spaces; common windows are adapted to act as ceilings and floors, and reading levels twist and break apart as the library breaks above the skyline.

Memory house is also integrated with the adjacent building, inserting a new floor that houses the program’s collection of books and other stimuli centered around subjects of human mentality.

level_00

level_01

level_02

level_03

level_04

level_05

level_06

level_07+08

Greenpoint Theater

GSAPP Technology Systems Studio - Theater - Brooklyn, NY

developing sophisticated systems integration

2018

in collaboration with…. Adina Bauman, Lena Pfeiffer, & James Piacentini

A 3 month intensive architectural project complete with fully articulated SD, DD, and CD submission sets, the theater at greenpoint, aimed to fully integrate a newly programmed site on the Brooklyn waterfront with both adjacent parks and urban contexts. The project relies heavily on an open air plaza thoroughfare that bisects the building longitudinally as well as laterally. The public space activates further activates nearby Transmitter Park, as well as currently existing industrial-styled retail that composes much of this rapidly developing NYC neighborhood. Moreover, by lifting the building, the site finesses necessary flood plain precautions whilst utilizing the environment for better passive system integration and bioswale landscaping.

Formally, the lifted program heightens the dramatic experience of partaking in arts. The main auditorium theater situated on the topmost level is strikingly hung by dramatic industrial trusses that, in combination with the re-purposed warehouse brick facade, calls back to the site’s previous architectural history.

The additional smaller venue blackbox theater intertwines the programs above and below, delicately suspended beneath the base of the auditorium and protruding into the open air plaza. The blackbox’s marvelous reinforced glass floor allows the implication of interaction between city passersby and its unique program.

standout drawings & images…

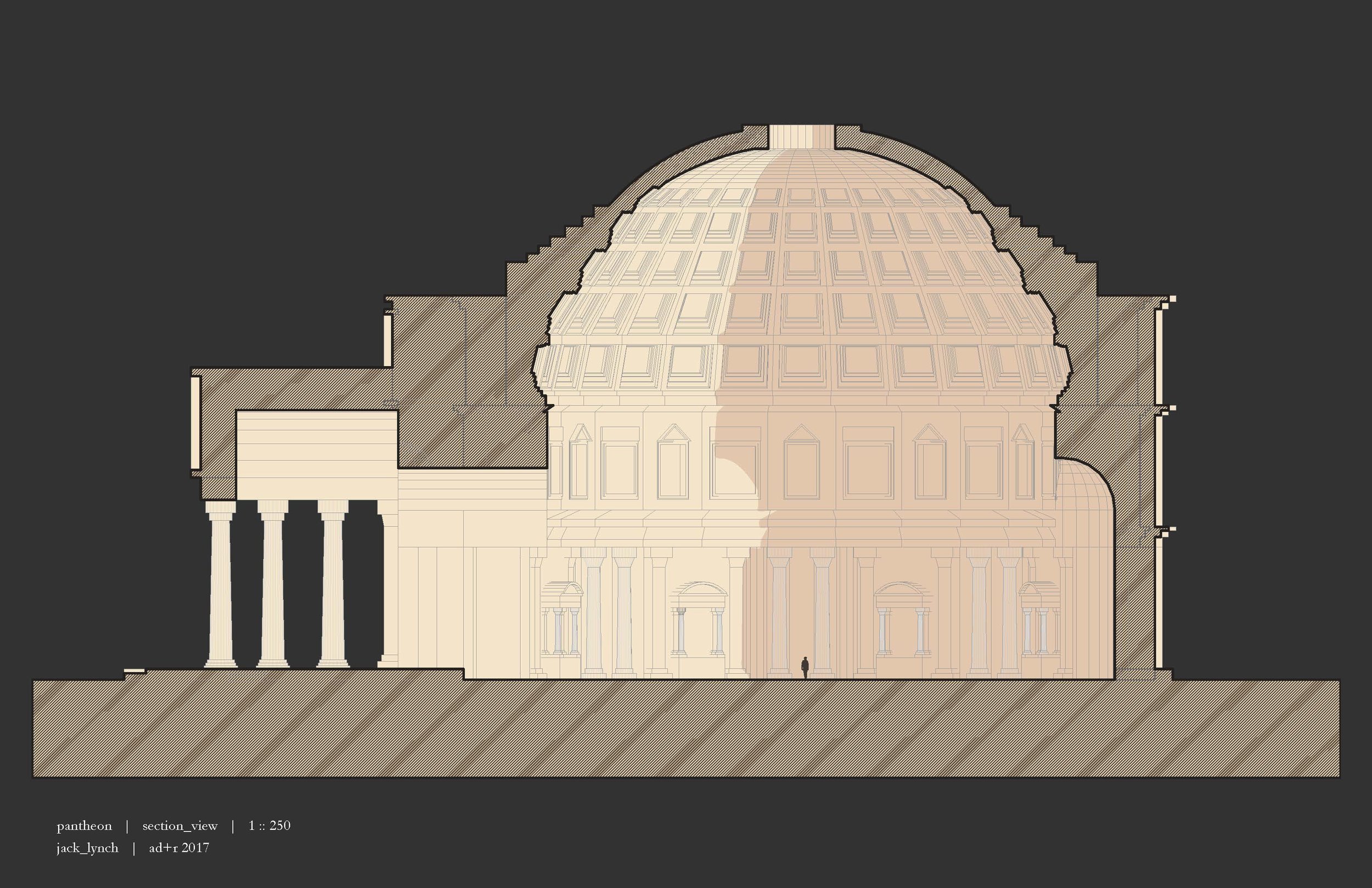

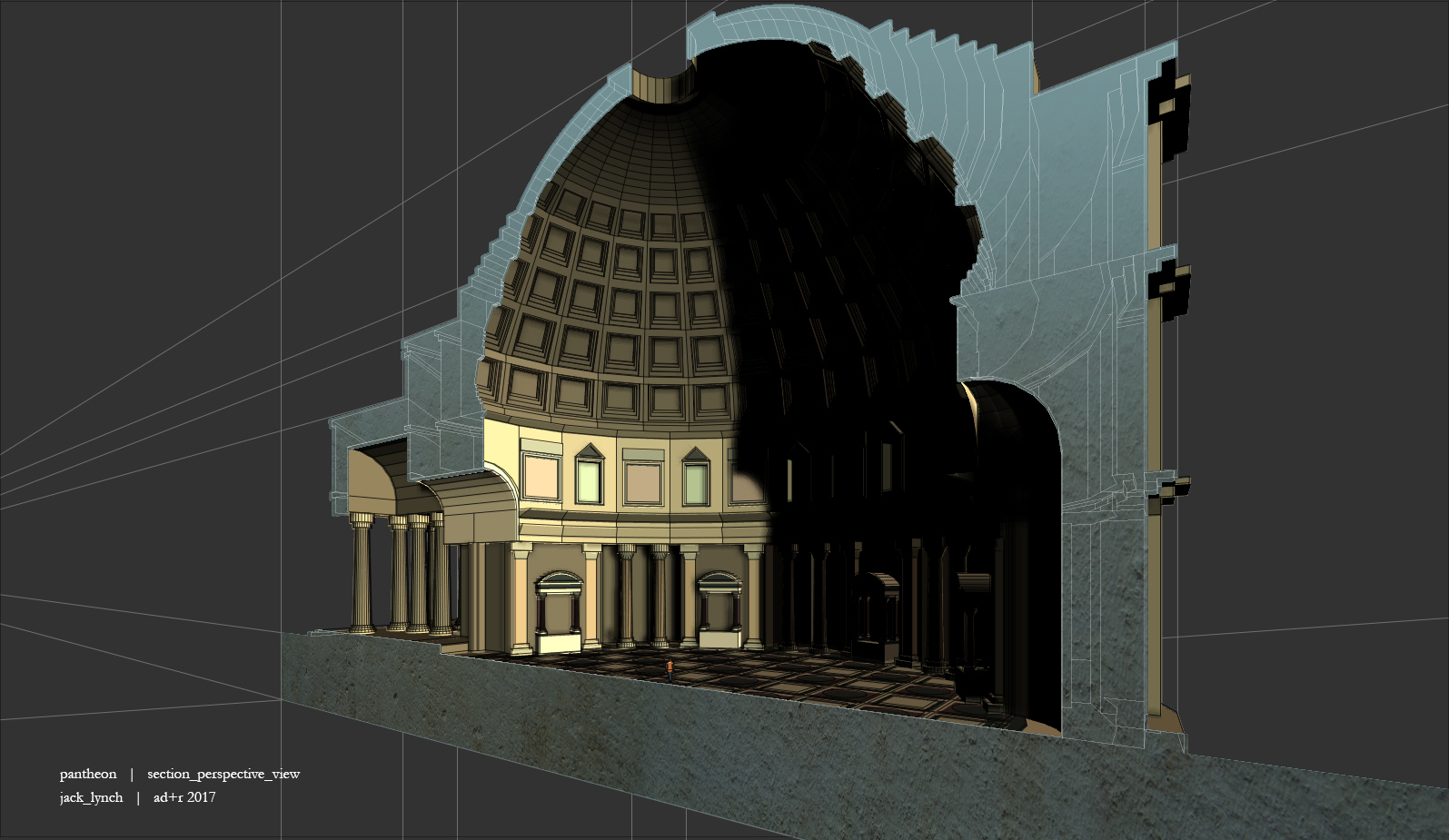

Advanced Architectural Design

GSAPP AD+R Studios - Assorted Projects + Drawings - New York, NY

in erinnerung an die klassiker, das neue

2017 - 2018

In memory of the classics... the new.

Highlighting the apparent return of post-modern styling in the 21st century, this collection of drawings, models, and mixed media animations addresses the rising popularity of post-digital modes and methods of representation. The focus of the work, James Stirling’s neue staatsgalerie, becomes a fitting symbol for reinterpretation. The vibrant colors and post-modern spatial effects surrounding an inherently classically inspired open-aired atrium heralded Stirling’s memory and reinterpretation of past art and architecture with present. In this likeness, neue staatsgalerie may once again be neue, its spatial and ornamental affects reinterpreted with the representations of today.

The drawing, kaleidoscopic (top left), envisions the original worm’s eye axonometric sketches by Stirling with the finesse and dexterity of advanced computer modeling, but with an ultimately flattened, crowded, and distracted visual complexity.

The additional “portable post-modern museum” model pushes the kaleidoscopic nature of a museum’s curation in tandem with its kitsch, consumerist undertone. And ultimately, the supplemental short animation, stirling’s dream sequence, ties together modern visual media and popular television motifs with Stirling’s atrium, the post-modern decor, and the classical artwork residing within.

additional work…

Lake House

GSAPP Ultrareal Rendering Studio - Lake Retreat - Catskills, NY

a bespoke residential retreat

2019

in collaboration with… Dalton Baker + Jake Gulinson

A retreat lake house located in the Catskills, this 2 bedroom residence was designed in tandem with the rocky shoreline. The house is intended to be constructed around an existing monolithic granite boulder that would be cut and polished into the shared kitchen and living space’s main feature: a polished, one-of-a-kind counter-top bar. The bedrooms, shared bath, and study are all kept isolated within a second internal space to highlight the procession from the entryway to the living space and exterior dock overlooking the lake vista.

Preliminary Work…

Exo-Mod

GSAPP Modular Fabrication Studio - Housing - North Bronx, NY

pre-fabrication, housing, + trees

2020

in collaboration with…. Dalton Baker

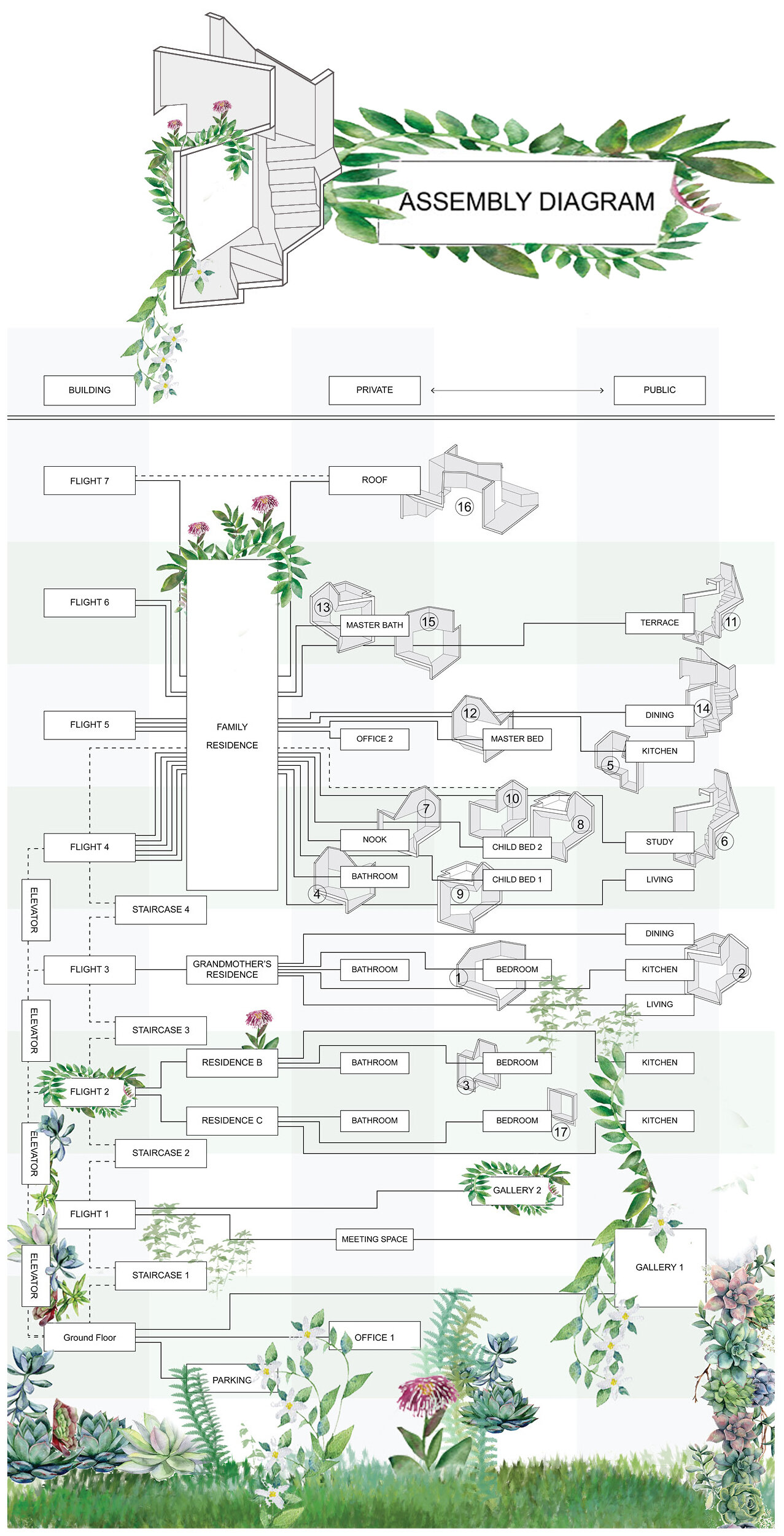

Consider the fold…

an exploration by Jack Lynch + Dalton Baker

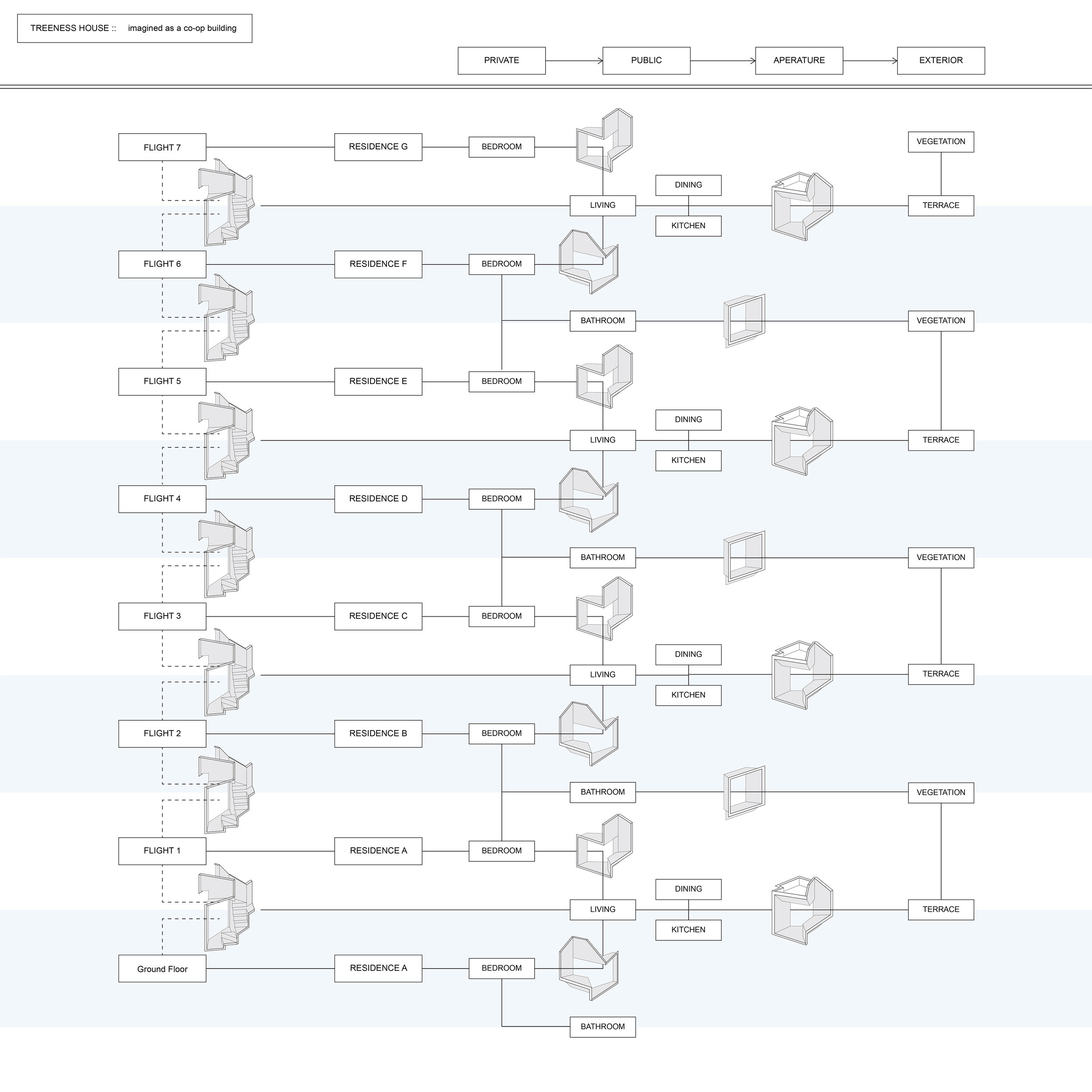

Akihisa Hirata’s Treeness House in Tokyo, Japan, is a compelling model for innovative architecture and nature working in tandem to develop space. It successfully houses multiple generations in one home, hosts a gallery space for art, and creatively folds the facade of the building back at various points to create unique spaces that bleed nature from the exterior, in - and vice-versa. The stairs and the pleats that create the living ecosystem of Treeness House, serve as connections to the rest of the building’s spaces that envision various scenarios that could be re-interpreted as a fully functioning modular system. The goal being to replicate the thesis of Hirata’s residence without duplicating any particular aesthetic. Consider a pleat. A fold in space that pivots all vectors towards a new direction. Eyesight, movement, even gusts of wind can all be pushed beyond the confines of “enclosure” when the concept is broken down and folded. The origami of architecture serving multiple functions. If pre-fabricated modules for residences could be thoughtfully designed in a similar fashion, then perhaps nature in our growing sustainable future can begin to metamorphose the construction and assembly of space. Better yet, over time folding away at how urban dwellers occupy the confines of their homes and interact with available pockets of nature.

The first iteration of the module system utilized the idea of the co-op to create apartments that had shared communal spaces. The system prioritized an 8’ - 8’ modulated grid, with a series of folding panels that could begin to carve out spatial arrangements within the overall layout. The carving nature established by the panels created an operable pleat that allowed the singular “unit” to blossom. This culminated in several different layouts, redefining the approach towards central circulation for buildings with multiple non-related occupants. The core circulation, like the interior modules, wove between nature and pathway, working towards bringing green space into both the private and public spheres of the building. However, the rooms’ folded panels lacked the ability to be customized and changed. To counter this, an adaptation towards a stronger post-and-panel system - akin to the living structure of plants that branch out and intertwine in intricate arrays and patterns. Moreover, this system would allow for development and change over time, a shared commonality between both the nature and the occupants invited to live in the spaces.

In this isolated iteration, the module systems are developed to accommodate multi-generational families in one apartment, thereby further the argument to allow the modules to grow and change over time so as to reflect the evolution of the family. By creating a baseline of every apartment beginning with double height spaces, occupants may choose to fill the larger spaces in with nature, begin development on a second floor for occupancy, or a mix between the two to better permeate the many lifestyle possibilities. The system creates a spectrum of different modular pieces, from full room sets, to additional planters and gardens, to smaller planter attachments that could be added over time using a patented track system. Furthermore, by enlarging the module from an 8’ - 8’ - 8’ grid to a 10’ - 10’ - 10’ layout, the spaces were given more room to breathe, establishing a deeper synthesis with the integrated nature components.

On a more specific scale, the system explores how nature can actively become integrated into each module. It recognizes the opportunities to look at how planters and green spaces can be used in different apartment and lifestyle scenarios to create green shared spaces for a broader audience of dwellers. This includes reintroducing the active presence of nature in any shared circulation spaces. Modules themselves could open up to become two or three modules rather than be contained into one 10’ - 10’ - 10’ grid. For instance, a bedroom that opens up into an office module with a folding desk, thereby allowing larger open floor spaces in an otherwise tight two module system. Or perhaps the entry way, with its sliding glass panels, becomes an extension of the outside to the two planter modules in front of them. With this system, the modular units sufficiently reflect the thriving ecosystem of nature - constantly pushing and pulling borders and boundaries to increase sunlight and sustainability. All in all, building towards a more sustainable future for living.

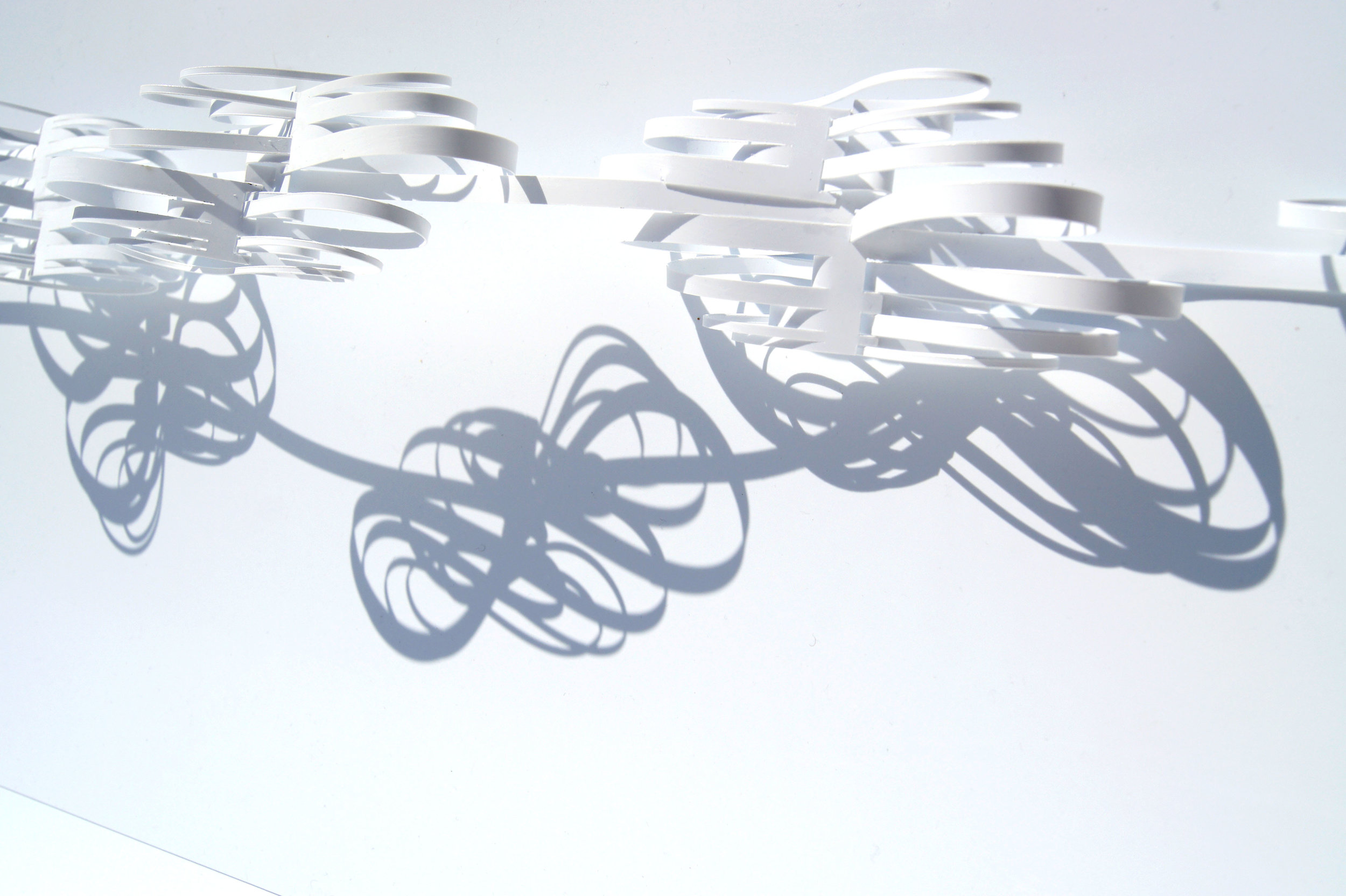

Echo Box

GSAPP Acoustics Studio - Installation - Flatiron District, Manhattan, NY

a pop-up acoustic installation

2017

Simple Pier

GSAPP Core I Studio - Pier - East River, NY

a reconstructed wetland initiative & urban exhibit

2017

Located just off 6th St., simple pier is a low-floating boardwalk pier along the East River that intersects the various growth stages of a long-term reconstructed wetlands plan. The pier exhibits close environmental encounters via apertures in the floor along the walk.

Additionally, the bank of the pier operates in tandem with the walk. Whereas the pier prominently puts the brackish flora on display, isolated aquarium tanks organized within an open urban plaza by the pier’s entrance would exhibit the fish and fauna species that thrive in the local tidal marsh.

The aquatic tanks are envisioned as recycled water cisterns, an immediate icon of the relationship between New York City and water. Moreover, the display aquariums would similarly be connected to the wetlands wastewater pipeline infrastructure, thus keeping with an adaptable and re-usable cycle.

Lastly, because of the projected long-term growth for the wetlands’ wildlife, the pier and its plaza would only exhibit local nature as it becomes prevalent. Throughout the first phases of development, the pier and plaza is displayed barren or empty, an evocative call to passersby + citizens that there is much sustainable work to be done to achieve space worth propagating and aesthetics worth displaying.

14th St. Subway Station

GSAPP Core I STudio - L-Train, NYC Subway - 14th St., Manhattan, NY

inverting urban weight in infrastructure

2017

Subway stations, in their purest practicality, work. There are many measures architects may take to assert a design, or a style, or an idea, towards the public, and with great success; however, one must accept that such interventions are fundamentally assertions of artistic representation, ultimately tacked onto a fleeting spatial hideaway beneath the city. The true room for spatial improvement in these spaces are: ingress, egress, and seating.

Because of this realization, the final design of the 14th St. Subway Station narrows its focus directly into a large culmination space - the atrium - partially set back from the immediate line of the subway. Think Grand Central Station. The space is voluminous, and open from the epicenter outwards. Its highlight is the ceiling, a massive, 70x25 foot cement rock, seeming upheld by an array of randomized curtain windows separating the border of the space from the excavated earth two feet set back. The weightless rock, my single, artistic addition tacked above this spatial space, consolidates the metaphor of life beneath a city resting on earth, and the construction processes necessary to achieve such feats.

The construction process would be as follows. First, the negative of the overhead cement for the atrium is excavated. Then, pylons and foundations are drilled deep into the rock of the island of Manhattan. The concrete is poured directly into the hole, held together by rebar and the tops of the drilled pylons. Once cured, the excavation of the atrium and it’s subtly descending ramps from the East + West begins. As the earth is excavated beneath the cast rock, it remains supported by the foundation drilling and pylons, which are then used as complex mullions and filled in with glass, creating the effect that the surrounding curtain wall - a metaphor for the existence of the city above - is supporting the earth.

Two additional stairwells are added on either end to facilitate better flow and traffic..

a fleeting moment on the afternoon express ::

When my smile had crept upon her face,

my eyes diverted but our speed grew great.

Flying fast towards that place

where size knew not yet massive weight

draws the best from anxious grace

into a world of troubled fate

at which stop she departed and I kept pace

towards nowhere.

Corner House

GSAPP Core I Studio - Adaptable Preservation - 14th St., Manhattan, NY

transforming urban infrastructures

2017

At the intersection of 14th St. and 2nd Ave. is a simple apartment building, corner house. 7 flights, pre-war, + just about similar to every other walk-up within Manhattan. In an effort to maintain the efficacy of this building’s simplicity, similar simple rotation movements of folding hinges and pivot rotations were added and caressed into the existing facade. Windows, bays, channels that define the ornament of the building shift and rotate so that over the course of a 24 hour day, various public + private spaces are activated within and beyond the realm of the building. The iterations, in their complete ensemble, cater towards 1 of 3 time periods :: morning, midday, + evening.

As the corner of 14th + 2nd slowly begins it’s alterations, the existing facade folds upwards, practically doubling the verticality of the building + revealing an activated athletic space properly situated within the realms of the geometries formed by the original ornament of the building. What’s left behind on the remaining sliver of exterior walls below is a sleek curtain wall, very much modeled as the ghost of the original building whilst it takes on a transformed ‘extra-ordinary’ state for a select few hours in a day.

With this project, the corner is allocated room to breathe. It may be experienced either in it’s original state, or in a new + invigorating state, both of which are just as exciting + beautiful as the other.

Flying Machines

GSAPP Core I Studio // WashU Core Studio II

interacting with air and light

2014 / 2017

RotoKite 02 | GSAPP, Core I Studio | 2017….

The form and subsequent floating function of RotoKite, 02 began with the inspiring drawings of mushroom spore prints. Performed by fungi enthusiasts, a mushroom left atop paper or glass in appropriate conditions releases it’s reproductive spores into visually appealing 2-dimensional patterns. This flowering image, coupled with the cyclical life nature found in select mushroom species, spawned the initial concepts for a folding form that could float wistfully atop any viewers below.

Originally conceived to ascend into space, modules of folded bristol were assembled in an overlapping conic form that could expand and contract in a blossoming fashion to receive heat from a flame source suspended beneath it. Logically, the paper rosette would rise with the heat and ascend gracefully. The modules were later re-analyzed into different media, assembled out of watercolored parchment paper and bass wood for a sturdier structure at a similar weight. Upon realization that the heat necessary to lift the object into the air was unattainable without drastic measures, the rosette was re-approached in its expanded state, wherein the later anticipated path of descent yielded a graceful spin downward that emphasized the points of the geometries. The rosette was clearly better suited for a floated fall rather than a simple rise. To better stabilize the flight path, a smaller, similarly defined rosette was connected concentrically just inches above the larger spiral. The new addition also featured a decorated fabric to act as chute for further air resistance.

Lastly, decorative LEDs were intertwined within the open space of the rosette, hailing back to the cyclical, inspiring nature of the spores released from mushrooms that ultimately inspired the shapes.

RotoKite 01 | WashU, Core II Studio | 2014….

An exploration in the merging of functional necessities and aesthetic forms, the RotoKite, v1 is a rotating form capable of achieving suspended flight in mild-to-moderate wind conditions via its creation of wind vortexes. the kite’s design pulls inspiration from numerous precedent studies of various wind-induced forms, namely the archaeological remains of prehistoric pterodactyl wing structures

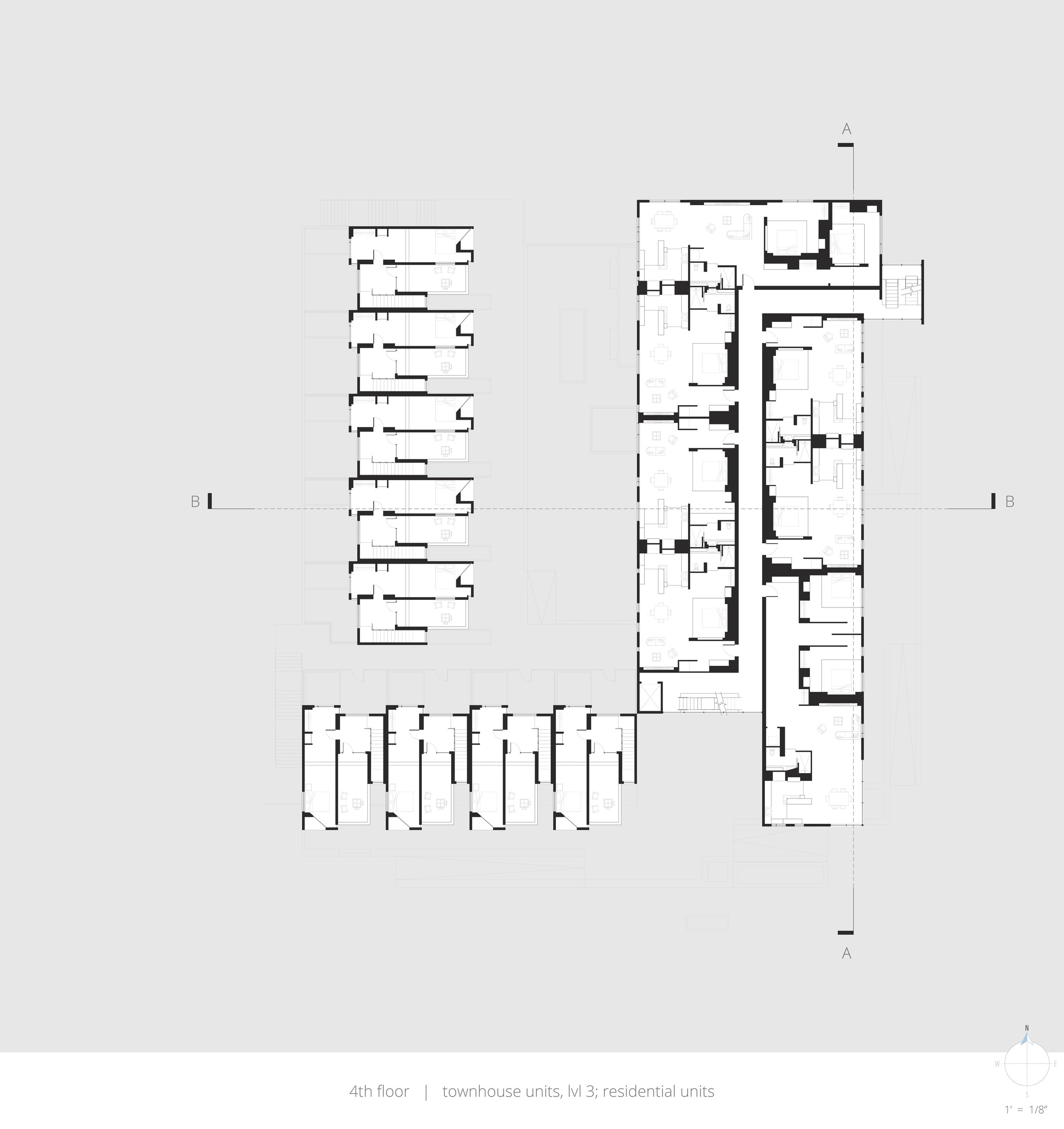

URBN plex

WashU Adv. Studio IV - Housing - Delmar Loop, St. Louis, MO

nostalgic luxury living

2017

Located on the northwest corner of the intersection of the Delmar and Skinker boulevards in St. Louis, MO, this housing project aims to situate a medium-rise residential building into a niche real-estate and developer market. Once named one of the 10 best streets in America, the Delmar Blvd. Loop is an eccentric, kitsch-driven atmosphere that profits from visiting outsiders and demarcates a clear socio-economic divide between its north / south neighborhoods.

Ultimately, the goal of this multi-use housing venture - playfully coined as urbn-plex - was to meet the demands of ambitious real estate developers all the while successfully integrating mixed-unit housing typologies to better integrate the stark divide between the site’s north and south borders. The formal attributes and ornament that detail the exterior of the complex cater towards the nostalgic aesthetic developers have embraced in storefronts along the street in recent decades. These moments are then re-evaluated and adapted to generate a successful merging of housing types that create internalized communities with access points to all the surrounding neighborhoods.

The living spaces include a homely collection of townhouses that connect directly with the street, all the while linking to a private elevated courtyard that connects the low-rise residences with a tower of 1-3 bedroom units.

Tiered Reflections

WashU Adv. Studio III - Landscape Architecture - Elephant Rocks State Park, MO

communal retreat center

2016

Located within the confines of the unique Elephant Rocks State Park in rural Missouri, tiered reflections began as an intensely concentrated study of the natural environment within the expansive site. The main feature of the park is a monolithic granite tor that climbs above the forest, prominently displaying large granite boulders resembling an imaginary herd of elephants.

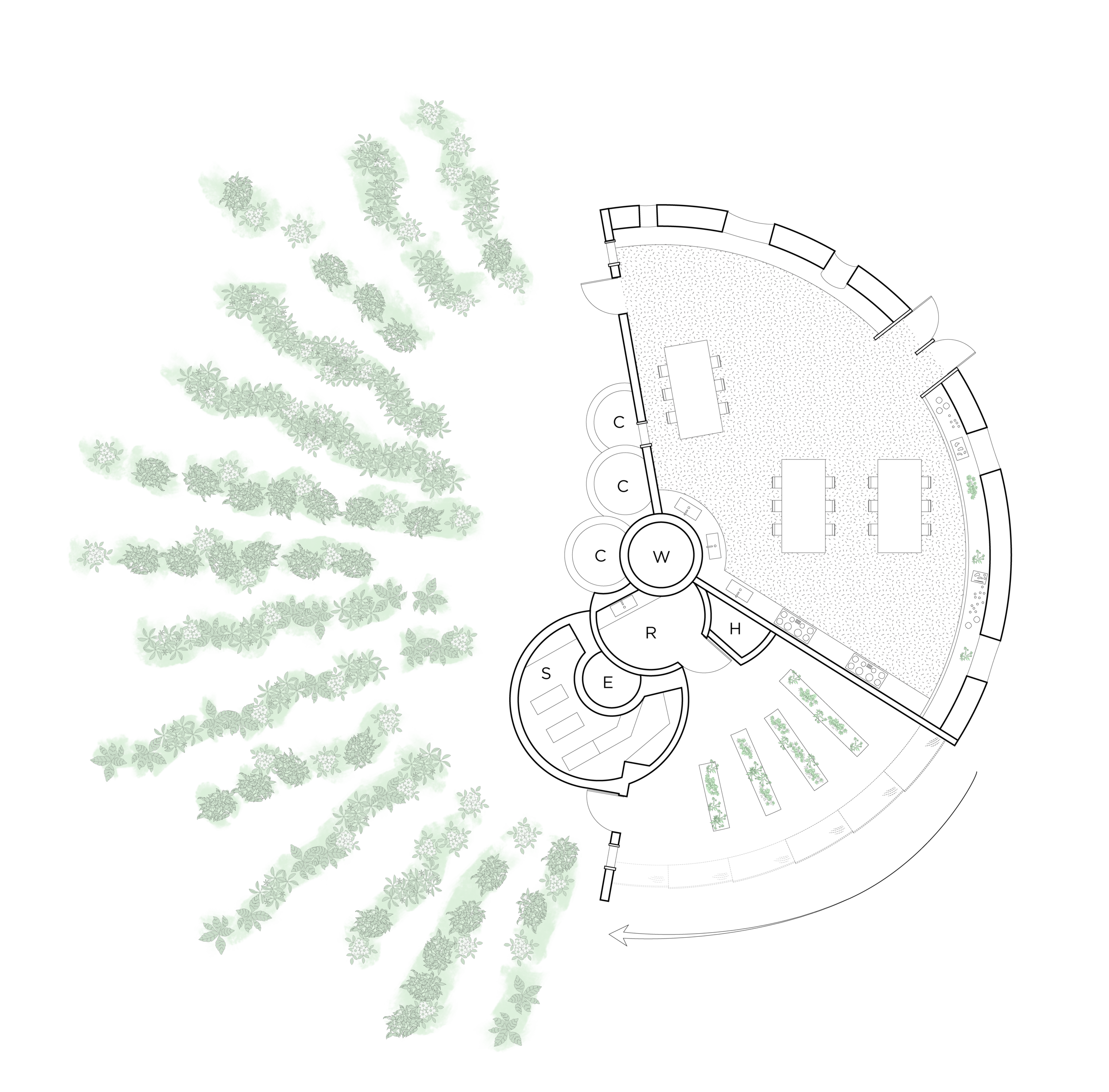

The site also has a rich history as privately owned granite quarries prior to their abandonment and acquisition by the state. The remnants of these quarries are two self-contained water reservoirs that attract environmentalists and will serve as the focal point for the design of an educational retreat center.

The retreat center comprises a set of 4 unique residences dispersed around a central hub. Visitors are encouraged to interact with the site, reflect, produce, and ultimately share their work with other occupants.

Four terraced water features are additionally landscaped to follow the geological topography of the two rock tors and quarries. The terraces are constructed with relation to the site’s hydrology, accumulating thin spans of stagnant water that reflect the scene of the sky above, becoming a path-like source of inspiration for the retreating community of 1 geologist, 1 artist, 1 academic, and 1 lay person.

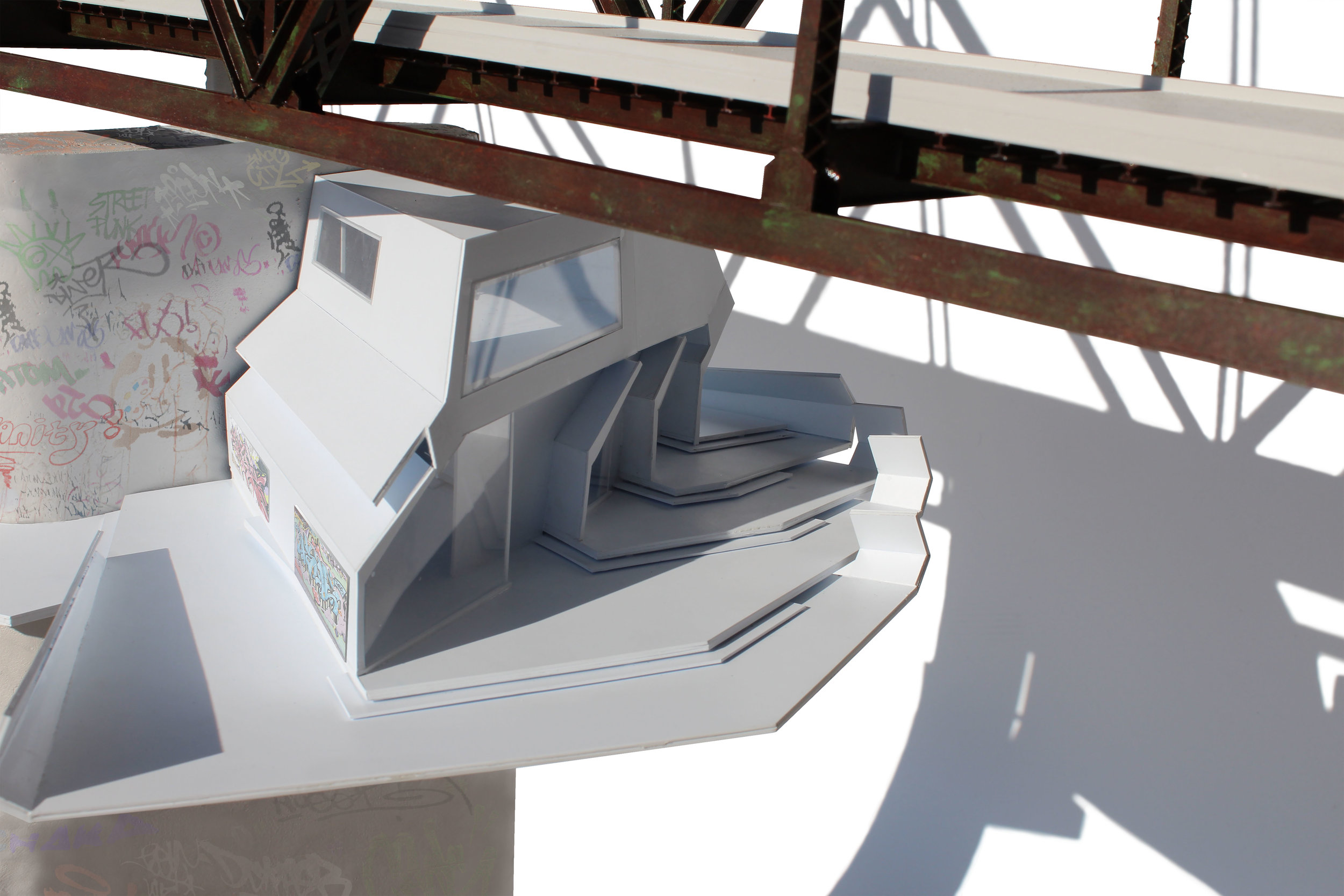

Graffiti House

WashU Adv. Studio I - Observatory - Chain of Rocks Bridge, MO

curating art + residency

2015

A project centered around the site of the Mississippi River, graffiti house uniquely situates itself above the river by attaching itself to the underbelly of the historic Chain of Rocks Bridge. This single person residence doubly functions as both home and museum, integrating itself vis-a-vis program with the bridge that supports it.

The intent of the structure is to house an urban art historian, one in charge of operating the coexisting gallery spaces that collect and project the incredible collection of graffiti present on aged urban infrastructures such as the bridge above.

Moreover, the particular formal attributes of planes and faceted faces that make up both the house and it’s elongated access ramp are intended to provide increased surface area and public accessibility to an otherwise private institution. This allows the continuation of such graffiti to ebb onto the structure itself, ultimately demarcating the residency’s program to visitor’s of the historic site overtime and thereby continuing the public conversation regarding graffiti’s role in the art world. Should it be promoted and preserved, or does that take away from the scandalous nature it seemingly yearns for? This question is further exemplified via the project’s delineation between public and private spaces, using the monolithic cement pylon of the bridge as a stark dividing line accessible to artists.

initial phenomena studies…

Vertical Greenhouse

WashU Core Studio III - Greenhouse - Soulard, St. Louis, MO

preserving urban ecology

2015

In learning to interact with ecology, climate, & other natural phenomena as inspiration for a systematic building, the project began at the scale of an isolated seedling. The sub-project, plant terrarium, saw a continuous development of form and systems integration during the maturing stages of the given plant, cyclamen persicum. The result is a fully functioning and self-sustaining enclosure, moderately scaled and assembled to adorn a desk, coffee table, or counter. The integrated systems include water collection, drip irrigation, cooling ventilation, and adaptive shading that all contribute towards the plant’s growth.

In jumping scale to that of a building, an urban, vertical greenhouse was designed to doubly function as both an urban garden and a local community center. The selected site is located adjacent to an I-44 W exit within the historic Soulard neighborhood of St. Louis, MO.

Quite simply, green house is a twisting vertical composition whose form emphasizes: 1) the inversion of height & growth, 2) the interplay between functional construction & design aesthetics, and 3) the interaction between nature and urban development. The triangulated facade is structurally relevant in this regard, narrowing in its contact with the earth and expanding upwards to encapsulate the necessary living systems for the ecological flora the structure houses.

inthecity

WashU Adv. Studio II - Urban Design - Florence, Italy

digital urban design theories, pt. 01

2016

Framing a view for the city of Florence, Italy via the lens of social media, inthecity explores how people, tourists and inhabitants alike, experience and share perceptions of their surrounding urban contexts. We see that as users upload photos to a greater global communications network, the interstitial spaces within city are broken down, abstracted, and adapted into new ideas of understanding and participation for all.

The New Social Life

WashU Adv. Studio II - Urban Design - Florence, Italy

digital urban design theories, pt. 02

2015 - 2016

Consider a bench. How do you sit? Why do you sit? What do you do while you’re there, and for how long? Do you even sit at all? Surprising as it may sound, the questions are far from as silly as they sound. A person and a bench have a rich, complicated history, one that fluctuates in functional use and usage rate over any given number of factors. Consider a more specific example: the bench outside of a high-trafficking library. Actually, more ledge than bench; a dividing partition, extended exactly thirty-two inches off the ground, grass on one side, walkway on the other. In the time spent observing this public ledge-bench outside of Olin Library’s front entrance on Washing University in St. Louis’s campus, a place where social interaction between young learning individuals is supposed to thrive in support of the educational environment, scores of individuals – students, professors, and adults alike – were performing the exact opposite of their social expectations. At 3:00 in the afternoon – the public area’s peak hours – occupants sit and remain both isolated and fixated on their own technological devise (current devices for most; designed within the last 5 years). Of the approximately eighteen persons occupying the space for longer than five minute stretches of time, there are at most 3 observable social exchanges. In this space, the technological devices are in control.

This ledge-bench and its surrounding area outside of Olin Library is exactly the type of space William H. Whyte would have loved to study for his published work and accompanying film documentary titled The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces (1980). In this in-depth series of studies, Whyte and his team, The Street Life Project est. 1971, dutifully investigated “the behavior of ordinary people on city streets – their rituals in street encounters, for example, the regularity of chance meetings, the tendency to reciprocal gestures in street conferences, [and] the rhythms of the three-phase goodbye” (Whyte 8). In the process of determining what spaces work, what spaces don’t, and the respective reasons why, Whyte ultimately came to the implied conclusion that the social interaction phenomena surrounding public spaces were inherent and human courses of action that have rarely changed over time despite architectural and design evolution. Just look at the widely successful public plazas in older European cities that have withstood the test of time and social evolution, like Piazza San Marco in Venice, Italy or Place des Vosges in Paris, France. “The best used plazas are sociable places” (17), “people reading, people eating, people talking, playing games… what attracts people most, it would appear, is other people” (18-19) and this sociability, Whyte seemed to believe, would never change.

It’s a bold statement, unfortunately, one could easily argue that the social and cultural patterns have seen an unprecedented deviation from this “inherent norm,” the result of a massive burst in technological change rather than architectural or design evolution. The Olin ledge-bench is the most successful public space within a two-three mile radius, yet from the time spent observing it, sociability seemed at a low and people seemed only marginally attracted to other people. If Whyte had the opportunity to observe this public space today, in 2015, then perhaps Whyte’s conclusion might have an addendum to account for technology, as it exists now rather than thirty-five years ago. That is, technology as an application of new social phenomena – both the objects upon which people are fixated and the social conditions the objects establish via their use. Discovering this addendum is the overarching goal of this investigative paper.

* * * * *

In the simplest of terms, Whyte believed that people are attracted to other people, but is this truly the case? Or, at the very least, has this belief become outdated in recent years because of prominent effects on sociability from technological evolution? Spatial attention and sociological theory are core principles that can relate back to an individual seated, say, on a ledge outside of Olin library. An article by researchers Kaitlin E. W. Laidlaw, Tom Foulsham, Gustav Kuhn, Alan Kingstone, and Dale Purves titled “Potential Social Interactions are Important to Social Attention” (2011) delves into sociological theory with an experiment that measured participants looking behaviors sitting in a waiting room, either in the presence of another person (a confederate in the study) or in the presence of the same person in a backdrop recording on a display screen. The study found that participants frequently looked at the screen of the videotaped person and seldom turned toward or looked directly at the live person. They documented both overt and covert gaze inclinations, with overt being defined as direct social gazes – focused, it should be noted, on the face, not the body – and covert being defined as peripheral gazes minimally acknowledging the other subject’s presence. In short, the study defines that “the potential (or lack thereof) for a social interaction to emerge may cause either 1) an increase in looking behavior when one knows that the other person cannot return their gaze or 2) a decrease in looking behavior when mutual gaze is possible… the simple act of introducing the potential for social interaction influences many measurable behaviors” (Laidlaw et al.).

The research indicates a number of things. First, people seem to not be, as Whyte would like to believe, attracted to other people; however, it can be concluded that, at the very least, people are interested in other people. With both the live and videotaped confederate, covert glances were recorded to occur much more often than overt gazes or baseline gazes at selected baseline objects in the waiting room. The high proportion of covert looks indicates that the second individual in the room does, indeed, interest the participants. Yet the fact that the recorded confederate on the screen attracted more attention than the live one cannot be ignored, and raises the question of whether or not people are more attracted to the presence of a screen – a application of technology present in almost all current forms of technology as an object – than the presence of a person.

Professors Anabela Mesquita and Chia-Wen Tsai wholeheartedly agree that yes, people are very much attracted to screens more so than people in their published text, Human Behavior, Psychology, and Social Interaction in the Digital Era (2015). Moreover, it’s not what’s necessarily on the screen that’s important either, but rather, the size of the screen that attracts the interest of the users. Inspired by former research claiming that, “different display characteristics may significantly affect the psychological importance of information displayed,” Mesquita and Tsai ultimately rebuked the correlation of larger screen space and user attraction, claiming instead that “user response to media information is usually preferred using screens of the average size” (131). The average size screen in devices as of 2015? Approximately six inches, weighed to such a short diagonal measurement due to the surplus of smartphone screens that dominate the technological market. And they are, indeed, favored, since more than a majority of the occupants in the Olin ledge-bench space were using smartphones rather than other devices.

So consider the smartphone. A research done by Tali Hatuka has found that smart phone users have regarded the public space differently as compared to normal mobile users – wherein “normal mobile users” refers to people using outdated phone technologies (i.e. non-smartphones; flip-phones). “These users are walking around the mall or to the train stations in their little bubble, thinking that they have their own privacy by detaching themselves from the real world” (Badger). Also stated, “it has caused people to be unaware of their surroundings, easily forgetting things they have walked past 10 minutes ago.” Moreover, smart phone users are more likely to run through their phone for directions instead of asking from strangers, promoting the device as the immediate associate for socialization rather than the surrounding society. This implied “detachment” infers the individuals’ own establishment of private space in an otherwise public setting. Hatuka and Badger, who writes on him, are led to believe that these issues will ultimately lead to a loss of human touch and a downgraded sense of awareness of the surrounding space – both the social space and the literal, existing designed space. If Hatuka’s statements hold true, then one could argue that people aren’t even at the very least interested in other people, completely refuting Whyte’s original postulate.

This poses the question of whether or not technology itself is at fault for the apparent withdrawal of social interaction among the individuals occupying the Olin ledge-bench. If technology does indeed play a factor in sociological theory, then how could it be studied? Sociologist Katrina C. Hoop published an article in 2012 called “Comte Unplugged: Using a ‘Technological Fast’ to Teach Sociological Theory” that delved into the cause-and-effect relationship between a student and his ready-at-hand technological devise. Hoop’s research can develop many parallels to the Olin ledge-bench, especially since the research primarily focuses on students form the current, technologically advanced generation. Ultimately, Hoop discovered that by embarking on “technology fast” (withdrawal from recurring technological usage), students were more engaged with social theory lessons and ideas in the educational setting than before. Of course, this only proves that an abandonment of technology is capable of fostering educational interest; however, the result can be extrapolated to prove that a removal of technology is capable of fostering any type of interest, including a social one.

In this investigation, technology exists both as the object and a social condition, and the primary use of the average device is social media. So if fifteen of the eighteen occupants in the Olin ledge-bench space where using devices, an assumed half of whom were in one form or another partaking in the use of social media, then there still exists a type of socialization in the public space. Technological social media applications such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, Snapchat, etc. spark new forms of interactions hidden behind the veil of the screen, in a relationship highly similar to Laidlaw et al.’s studies with the live and videotaped confederate. What’s more intriguing is the primary difference these digital social networks have to offer compared to the living social network of the small urban space the technological objects are being used in. Digitally, the user is allotted a sense of choice. He or she may upload a photo of their own selection, may share a link they deem appropriate, may post a status they find fitting. The appeal of choice is enormous in the digital database technology has access to, and this presents the idea that technological social conditions present occupants with a selection pool that far outweighs the selection pool the literal space they’re occupying offers. Why should a person talk to one of the other seventeen Olin ledge-bench occupants when he or she can talk to one of their six hundred and twelve friends on Facebook? Why bother observing one of the three couples walking by when they can observe the latest gossip of the hundreds of celebrity couples via Buzzfeed? This suggests another addendum. People aren’t attracted to other people, but rather people are attracted to what interests them.

If the social actions of these small urban space occupants – the rituals, as defined by Whyte in Spaces (26) – can be re-illustrated into technology use – again, both in object and social condition – then the same might be said of the small urban space as well. Or, more precisely, perhaps the “new evolution” of socialization present in technology deserves its own, new small public space: small digital spaces we might define it. A space visually similar to Dennis Crompton’s Computer City drawing (ca. 1964) which portrays an urban metropolis as a programmable network that responds and adapts to the activities of the city’s space. (Figure 1) It’s all hypothetical, as were most of Archigram’s self-imposed projects; however, Crompton’s visual display of the city is evocative of diode circuits and electrical substation design elements. Archigram was heavily inspired by the birth of the widely accessible technology we now have today for their designs, and this is obviously apparent in the abstract alternative to Peter Cook’s Plug-In City (ca. 1964) that is Computer City. Since Computer City is a diagram of system design in abstract space, the illustration can be appropriated to diagram technological social conditions in existing, concrete small urban spaces – a mapping of the larger, digital selection pool for occupants in the smaller selection pool of small urban spaces. It would be in this abstract realm of data systems that occupants are partaking in social activity – people seemingly attracted to other people – whereas in the physical realm of small urban spaces, socialization can be seen as dead, replaced with the notion of people attracted to what interests them rather than other people.

The small digital space is both similar and distant from Whyte’s original small urban space. The activities that occur remain the same, “people reading, people talking, playing games…” (Whyte 18), just translated differently, in the medium of a different space. This does either one of two things: 1) it upholds Whyte’s ultimate conclusion that social interaction phenomena surrounding public space (wherein public space is the digital space of technological social conventions) is inherent and a human course of action that has rarely changed over time, or 2) it disregards Whyte’s ultimate conclusion because the public space no longer exists in the physical form, with the concrete, small urban spaces showing a complete lack of socialization beyond the device. It becomes a matter of perspective. Shlomo Benartzi and Jonah Lehrer write in their book, The Smarter Screen: Surprising Ways to Influence and Improve Online Behavior (2015), that despite the serious effects smartphones have had on society, “human nature [has] evolved over millions of years; it’s unlikely to be transformed in a decade or two” (34). While they spend the course of the novel acknowledging that “the medium of information and decision making has changed [as have our interventions with such]” (7) they see the effects of technology as nothing more than new translations of the same inherent human values – including Whyte’s social ones. People are attracted to other people; people still occupy the small urban space; ergo, Whyte’s conclusion is valid, and no addendum is ultimately necessary.

But if one were obliged to believe otherwise, to fall in line with option two where the small digital space does not stand for Whyte’s small urban space, then could Whyte’s conclusion still be an acceptable interpretation? Perhaps using Karen A. Cerulo’s published article, “Nonhumans in Social Interaction,” it can be deduced that the occupants of the small urban space are just as, if not more, socially active in the physical space than the digital one. “Nonhumans” looks at sociological theory in a new lens, claiming that social interaction extends beyond the human level. “If developments in the field suggest that nonhumans – including animals, objects, images, and both memories and projections of the self and others – enter our analytical frame,” then are we not actively involving ourselves in a form of social activity?

Picture this. While walking by the Olin Library, I feel my handheld device vibrate with an alert, so I alter course and rest on the nearby ledge-bench. The handheld device soon becomes distracting, and I begin scrolling through Facebook and other “social media” applications – all the while keenly aware of the ledge upon which I am sitting. I show no physical signs of socially involving myself with the score of students, adults, and professors walking by, yet despite the attention to my phone and my immersion in the small digital space it provides, my peripheral vision, covert senses (Laidlaw et al.), and innate sociological sense (Whyte) makes me aware of every person that stops or hesitates near or around my seated area of occupancy. The implicit, possible potential of social interaction is present, expressed through inanimate objects such as the ledge on which I rest, the device on which I use, the walkway on which people pass, and the grass on which people sit. If Cerulo’s theories are valid, then social interaction still exists in the small urban space despite the outweighed socialization occurring in the small digital space overlaid on top; the primary difference is that this social interaction is implicit, channeled through inanimate objects including technology. It suggests yet another alternative addendum to Whyte’s belief: people attracted to other people via things [that interest them] rather than people simply attracted to other people.

While there has undoubtedly been a change in the individual’s perception of these small urban spaces, and alterations to what people are ultimately attracted to, the necessary comfort and need for social interaction – by any mean of its definition – still attracts people. This suggests a final reinterpretation of the design intent surrounding small urban spaces. Whereas before successful plazas and small urban spaces were designed around the concept of social congestion via open seating that appealed to draw people in for social interaction (on the premise of people attracted to other people), now spaces should be designed around the concept of social comfort via open seating that appeals to draw people in for implicit social comfort around the technological bubble (on the premise of people attracted to what interests them). The actual design of the small urban spaces remains the same in both scenarios, with the addendums proposed only establishing a shift in the causes for the final designs. In a way, Whyte addresses this shift as a simple fact – back before the technological bubble came to be. “The busiest places tend to be the places where one desires to be alone…” he narrates in his accompanying film documentary over footage of a man idly sitting alone and visibly talking to himself in a public space.

Because the final designs in both scenarios remain the same, with marginal readjustment in their causal interpretations, the design of urban spaces may continue to perform their one and only goal of being appropriately occupiable, nothing more, nothing less. “It is difficult to design a space that does not attract people. What is remarkable is how often this has been accomplished” (Whyte, film). There’s no need to over-complexify occupiable space, like John Portman’s design of the micro-urban space in the Westin Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles, which seeks to confuse and disrupt the cognitive processes of its occupants so as make them submissive to the design and forced to act fully within the space (i.e. it can be extrapolated that the design encourages interaction with the physical space rather than, say, the small digital space of technology abstractly overlaid on top of it [see Computer City]). (Figures 2, 3) The better solution remains in the simple – in what works – like the Seagram Plaza, which Whyte himself spent a majority of his time studying for Spaces. (Figures 4, 5) The subtlety of its open design and available seating continues to attract people to occupy the space, despite the occupants’ new trends in technological use when in the space.

Lastly, public spaces should avoid being designed as large public spaces. There’s a reason small urban spaces are deemed more successful, because of their more attune attraction factor, as dictated by Whyte. Though designers today may argue that larger public spaces offer the ability to promote even higher sociability via the use of programmable space in the larger area plazas, this ultimately neglects several key factors in social theory. By spreading out occupants, the desire for detachment from society (Badger) into handheld devices is reduced since there is little to detach from. Moreover, the larger area results in minimal nonhuman objects with which occupants can form implicit social interactions. The results are feelings of uncertainty and discomfort among occupants that lead them to seek out the comfort of smaller public spaces, again reinforcing the notion that while addendums to Whyte’s principle that people are attracted to other people may have come about, his ultimate conclusion that the social interaction phenomena surrounding public spaces is inherent and unchangeable remains valid.

Works Cited

Badger, Emily. "How Smart Phones Are Turning Our Public Places Into Private Ones." CityLab. The Atlantic, 16 May 2012. Web. 18 Nov. 2015.

Benartzi, Shlomo, and Jonah Lehrer. The Smarter Screen: Surprising Ways to Influence and Improve Online Behavior. New York City: PORTFOLIO, 2015. Print.

Cerulo, Karen A.. “Nonhumans in Social Interaction.” Annual Review of Sociology 35 (2009): 531-552. Web.

Francine K. Schlosser. “So, How Do People Really Use Their Handheld Devices? An Interactive Study of Wireless Technology Use.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 23.4 (2002): 401-423. Web.

Hoop, Katrina C.. “Comte Unplugged: Using a “Technology Fast” to Teach Sociological Theory.” Teaching Sociology 40.2 (2012): 158-165. Web.

Laidlaw, Kaitlin E. W. et al.. “Potential Social Interactions Are Important to Social Attention.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108:14 (2011): 5548-5553. Web.

Mesquita, Anabela, and Chia-Wen Tsai. "Human Behavior, Psychology, and Social Interaction in the Digital Era." IGI Global, 2015. Print.

Whyte, William H. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. Washington, D.C.: Conservation Foundation, 1980. Print.

Whyte, William H.. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. Conservation Foundation, 1980. Film.

Chapel House

WashU Core III Studio - Non-denominational Chapel - Clayton, MO

experiencing space and light

2014

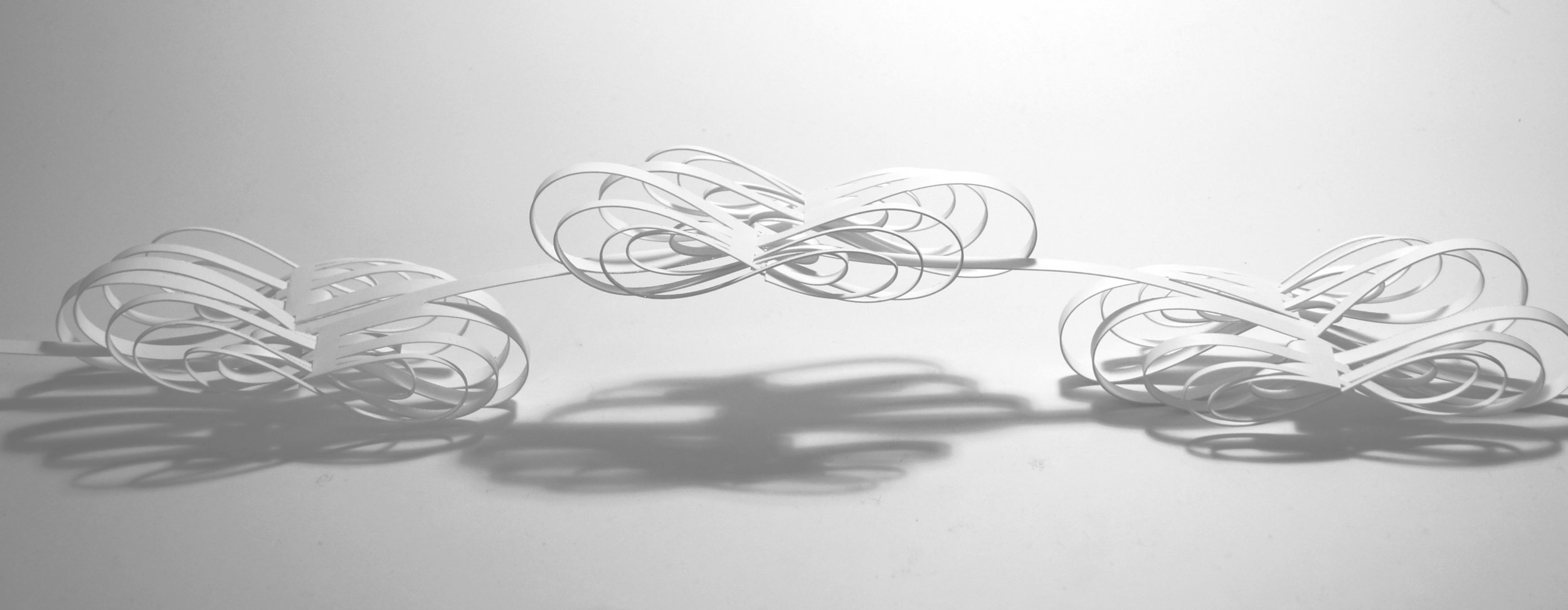

In learning to interact with light, shadows, and other natural phenomena as inspiration for spatial organization, the project began with a single module. Strips of paper interwoven into one another created unique curvatures that allowed for diffused light to creep past any screen assembled.

As the modules began to aggregate, they could be manipulated to act as partitions between spaces. By doubling the strips and creating alternating patterns, the boundary between the partitions denoting one side, the other, and the space between began to blur as well. Ultimately, this blurred boundary would be used as the parameters defining a non-denominational, programmatic chapel - for individual or collective worship - in the urban setting of Clayton, MO’s Concordia Seminary Park.

The result, chapel house, is a juncture of two dichotomous forms that reflect on both separation as well as unification. In the chapel’s form, there is a stark divide between the functional necessities of usable space and the primary area of worship and occupant experience. The sacred space follows the module light studies from before, while the allotted program spaces reflect the opposite in stark contrast, literally intersecting with its counterpart at the entrance. Between the two, the exterior urban setting is shut out from the private interior spaces.

Forest Park Pavilion

WashU Core I Studio - Observational Pavilion - Forest Park, St. Louis, MO

an observational space

2013

In an introduction to the methodology of design processes, this observational pavilion ideally set in St. Louis, MO's Forest Park pulls inspiration from the decomposing qualities found in local birch trees and numerous topographical and modular design forms.